Strategic overview and current political context

The removal of Nicolás Maduro from effective power has marked a significant political rupture in Venezuela, but it has not yet produced a clear or stable transition toward institutional normality. From an operational and security perspective, the current phase should be understood as a period of contested stabilization rather than a post-crisis environment. While the disappearance of Maduro as a central figure has altered the internal balance of power, most of the coercive, criminal, and administrative structures that shaped the Venezuelan risk landscape over the past decade remain in place. For foreign corporations, this creates a paradoxical environment in which new commercial opportunities are emerging while core threats to people, assets, and operations remain acute.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

Since Maduro was taken out of the political equation, power has gravitated toward an interim executive configuration dominated by figures from the former regime, notably Acting President Delcy Rodríguez. This leadership has focused on rapidly consolidating control over the security apparatus, state-owned enterprises, and key revenue streams, particularly hydrocarbons. The priority has not been democratic reform but regime survival through transactional legitimacy and pragmatic engagement with external actors, especially the United States. Recent shifts, such as the February 2026 amnesty initiatives and the symbolic closure of the El Helicoide prison, suggest a tactical liberalization intended to satisfy Washington while the underlying surveillance and intelligence apparatus remains operational. As a result, Venezuela’s governance model remains highly personalized, opaque, and unpredictable, with decisions driven more by political calculus than by legal or institutional norms.

Economic environment and emerging opportunities

Economically, Venezuela remains structurally fragile despite renewed external interest. Inflation remains extremely high and access to foreign exchange remains uneven and politicized. Crucially, under Executive Order 14373, oil revenues are now funneled into U.S. Treasury-controlled “Foreign Government Deposit Funds,” creating a new layer of financial gatekeeping where the interim government must request budget releases from Washington. While oil exports have increased modestly following limited sanctions relief, public infrastructure continues to deteriorate and public services are unreliable. Nevertheless, the collapse of domestic productive capacity has created significant gaps in supply, opening opportunities for foreign operators capable of managing high-risk environments.

The most viable commercial prospects are found in sectors characterized by high demand and minimal competition. The late-January 2026 reform of the Organic Hydrocarbons Law represents a major pivot, now allowing private companies to hold majority stakes and independently commercialize oil and gas. Infrastructure repair, including electricity, water treatment, telecommunications, ports, and airports, presents another area of potential engagement, though it is deeply entangled with political approvals and corruption risks. Under the new General License 46, these opportunities are strictly conditional on the exclusion of any entities linked to China, Russia, Iran, or Cuba, making geopolitical vetting as important as financial auditing.

Impact of emigration on the workforce

Venezuela’s large-scale emigration over the past decade has had a structural impact on local human resources. More than eight million people have left Venezuela, with a disproportionate share coming from the most productive age groups and from skilled and managerial professions. This has resulted in a reduced pool of experienced technicians, engineers, supervisors, and middle managers, alongside a degradation of institutional knowledge and corporate culture. While labor remains available in quantitative terms, companies face shortages of reliable, compliance-aware, and technically up-to-date personnel. Furthermore, the industry currently faces an acute technical crisis regarding diluents; following the break with Iran, firms must now leverage General License 47 to self-source these essential chemicals from the U.S. rather than relying on state-provided technical logistics.

Criminality and physical security threats

Venezuela continues to present one of the most complex and severe security environments in Latin America. Violent crime remains endemic, driven by a convergence of economic collapse, organized crime, and weak rule of law. Armed robbery, carjacking, kidnapping, and extortion are persistent risks, particularly in urban centers and energy infrastructure zones. The fragmentation of the central command following Maduro’s capture has emboldened “mega-bandas” and irregular groups, who increasingly operate as autonomous regional power brokers.

Organized criminal groups continue to operate with significant autonomy, often overlapping with or protected by elements of the state. For companies, this creates a blurred threat environment in which criminal and political risks are often indistinguishable. Demands for protection payments, interference in hiring decisions, and theft of goods are common manifestations of this convergence. Security forces may act as law enforcement during the day and participate in extortion or illicit activities at night, complicating threat attribution and response.

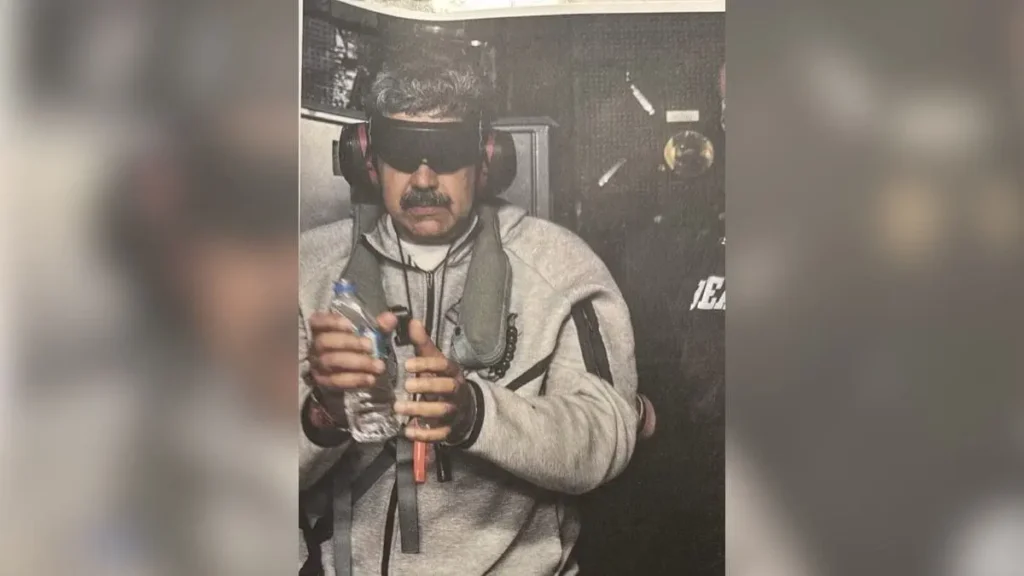

Political coercion, arbitrary enforcement, and detention risk

Beyond criminal threats, foreign personnel face non-trivial risks of arbitrary detention or intimidation by state actors. In the current transactional environment, regime holdovers may view foreign executives as “bargaining chips” for negotiations with Washington, making the risk of detention a primary tool of diplomatic leverage. Legal protection is weak, judicial independence is limited, and due process cannot be assumed. Administrative harassment through inspections, license suspensions, or sudden regulatory changes is another common tool of pressure. These actions are often selective and politically motivated, making them difficult to predict or contest through formal legal channels.

Corruption, integrity, and compliance exposure

Integrity risk is a defining feature of the Venezuelan operating environment. Corruption is systemic and deeply embedded in administrative processes. Permits, customs clearance, and procurement are all potential vectors for bribery pressure. For companies subject to extraterritorial anti-corruption legislation, this creates acute compliance exposure. The new regulatory landscape requires an even higher standard of “Sanctions-Exclusion” vetting to ensure that local partners have no hidden beneficial ownership involving sanctioned “East-Block” interests (Russia/China/Iran). Without strong due diligence, companies may unknowingly become entangled in corruption networks or sanctioned structures with severe legal consequences.

Protection of personnel and operational autonomy

The protection of people must be treated as the primary operational priority. Travel should be tightly controlled with mandatory risk briefings, vetted transport, and reliable communications. Assets and facilities must be designed as self-contained “islands of stability” with independent power, water, and satellite-based communication to bypass failing national infrastructure. A low-profile posture is essential, including strict controls on corporate branding and social media exposure. Personnel and their families must understand the security environment and their role in reducing exposure. Kidnap and extortion risk requires specific preparation, including access to specialized crisis response capabilities.

Due diligence, investigations, and third-party risk

Due diligence and investigative capabilities are central to risk mitigation. All third parties must be subject to enhanced scrutiny that specifically maps geopolitical links to prohibited foreign actors under the newest OFAC guidelines. Contracts should include audit rights and termination mechanisms that can be activated if risk thresholds are exceeded. From a strategic perspective, the most prudent approach to Venezuela is a phased, limited-exposure entry model. Initial engagement should focus on intelligence collection and relationship mapping. Expansion should only occur if political conditions and compliance frameworks demonstrate sustained improvement. Volatility should be treated as a permanent feature of the operating environment.

Conclusion

The post-Maduro phase in Venezuela does not represent a return to normalcy, but rather a reconfiguration of risk. The transition from minority to majority partnership rights in the energy sector offers high rewards, but these are balanced against the new complexities of U.S. Treasury-controlled revenue streams and strict geopolitical exclusions. Companies that choose to operate in Venezuela must do so with a clear understanding that success depends less on commercial potential than on disciplined risk management, rigorous due diligence, and the ability to rapidly adapt or disengage if conditions deteriorate.