SUMMARY

Brazil is experiencing a rise in political violence as the 2024 city elections approach, with incidents already occurring. These incidents reflect the ongoing polarization and insecurity from previous elections. The 2022 elections were marked by significant violence, including murders and arson by individuals contesting the results, culminating in the invasion of government buildings on 8 January 2023. Political violence also marred the 2020 municipal elections, with numerous attacks, highlighting the influence of organized crime in Brazil’s electoral process. This growing trend of political violence threatens not only Brazil but in Latin American neighboring countries and even in as the United States.

Rising Political Violence Ahead of Municipal Elections

Brazil has been experiencing an increase in political violence related to the upcoming local elections in October 2024. Historically, local elections, where people choose mayors and city councilors, are more violent than presidential and gubernatorial elections. The first incidents connected to the 2024 municipal elections indicate that the factors fueling violence remain unresolved. Even before the official campaign has begun, attacks have already occurred, highlighting the prevailing tension and insecurity.

On 7 May, former police officer and councilor Erasmo Morais (Partido Liberal PL) was brutally murdered with rifle shots in the city of Crato, Ceará. According to the Military Police, the crime occurred near the councilor’s residence. Witnesses reported that two men in a white pickup truck fired shots and then fled.

On 14 July, military police officer Clayton Gross Batinga, former deputy secretary of Public Security in Belford Roxo, Rio de Janeiro, had his car hit by at least four shots. Batinga, an ally of Mayor Waguinho (Republicans) and pre-candidate for councilor, managed to survive the assassination attempt.

The growing political polarization in Brazil exacerbates this violence, creating an environment of hostility and division that fuels attacks and threats against those who engage in politics. This escalation of crimes not only puts the integrity of victims at risk but also threatens the democratic process itself, which depends on a safe environment to thrive.

Political Violence During Brazil’s 2022 Elections

Political violence has been a feature of Brazilian elections, but it escalated significantly during the 2022 campaign. The presidential race between Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) and Jair Bolsonaro (PL) was particularly marked by violence, including homicides, intimidation, and aggression. While previous elections saw mainly local disputes, many severe incidents in 2022 were directly related to the presidential contest.

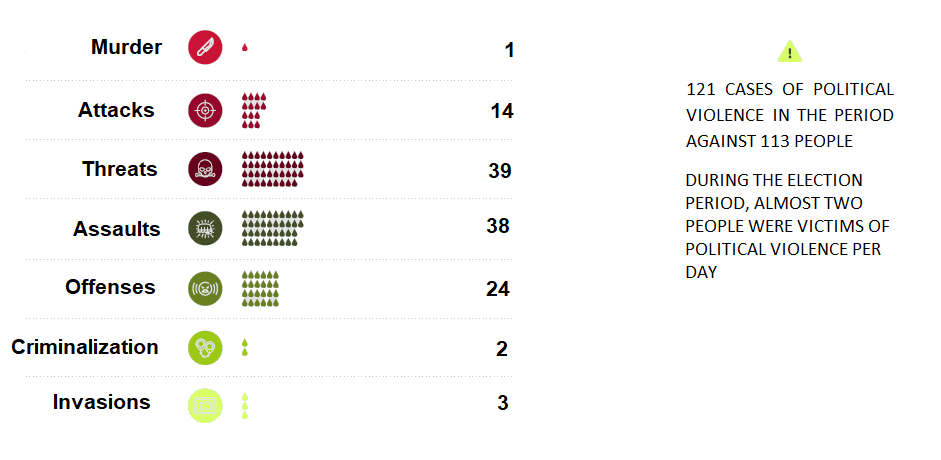

On 9 July, federal police officer Jorge Guaranho fatally shot municipal guard and PT member Marcelo Aloizio de Arruda during a birthday party in Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná. On 7 September, Rafael Silva de Oliveira was arrested for stabbing his co-worker Benedito Cardoso dos Santos, who supported Lula, after a political argument in Mato Grosso. On 2 September, military police officer Vitor da Silva Lopes shot advisor Davi Augusto de Souza in Goiânia, provoked by a pastor’s speech against left-wing parties. These incidents reflect broader trends reported by the Unirio Political and Electoral Violence Observatory, which recorded 40 deaths due to political violence in the first half of 2022. Leading up to the first round of elections, from 1 August to 2 October 2022, political violence surged, with 121 episodes documented, averaging around two cases per day. The targets were primarily political agents affiliated with left-wing parties like PT (Workers’ Party Partido dos Trabalhadores) and PSOL (Socialism and Liberty Party Partido Socialismo e Liberdade), according to the 2nd edition of the Political and Electoral Violence in Brazil survey by Terra de Direitos e Justiça Global.

Violence persisted beyond the elections. Supporters of former President Bolsonaro contested the results with protests across various cities. In Brasília, they set fire to seven cars and four buses and vandalized a police station. There was also an attempted bombing at Brasília International Airport involving a truck loaded with kerosene. Additional disruptions included pipeline destructions in Ariquemes, Rondônia, causing a water shortage, highway blockades in São Paulo, and attacks on truck drivers in Paraná. These violent acts culminated in the 8 January invasion of the Three Powers Square, where protesters vandalized the National Congress, the Planalto Palace, and the Supreme Federal Court.

Political Violence During Brazil’s 2020 Municipal Elections

When municipal elections are scheduled, a cycle of threats and violence against candidates, particularly for councilor and mayor positions, typically emerges. The 2020 municipal elections underscored this pattern, revealing an increase in political violence compared to previous years.

Between 9 and 15 November 2020, 45 incidents of political violence were reported, including murders and assaults, averaging six cases per day, according to the “Political and Electoral Violence in Brazil” report from Terra de Direitos e Justiça Global. From January to September 2020, there were 13 murders and 14 attacks, and from 2 September to 29 November, 14 murders and 66 attacks against candidates were recorded. This made 2020 the most violent year for candidates in Brazil, surpassing previous years.

Political violence in 2020 was also visible during live broadcasts. On 9 September, councilor candidate Ricardo Moura (PL) was shot in Guarulhos (SP) while live on social media, and on 24 September, Cássio Remis (PSDB), a councilor candidate in Patrocínio (MG), was killed during a live broadcast denouncing the City Hall. The Public Works Secretary of Patrocínio, Jorge Marra, was later arrested for the crime.

In June 2020, a march in downtown Rio de Janeiro against the Bolsonaro government turned violent when protesters threw rocks at police officers and cars on Avenida Presidente Vargas. There were also protests against the government in various neighborhoods and a demonstration in support of Bolsonaro in Copacabana. This event highlights the growing political tension and violence associated with protests in Brazil.

Organized Crime’s Influence

Felipe Borba, a professor at Unirio, argues that while the number of victims of electoral violence may be relatively low, its effects on Brazilian democracy are profound. Political violence deters potential candidates, disrupts campaign events, and facilitates voter coercion, particularly by local militias.

The influence of militias and other organized crime groups in the Brazilian elections, particularly in the municipal polls, is concerning.

Municipal elections are particularly vulnerable due to the proximity of candidates to local communities, where militias and factions exert territorial control over an area with a population large enough to elect a local representative, like a city councilor, or have a great impact on the decision of a major position, such as that of mayor. The groups can finance campaigns and sabotage opponents through threats, aggression, and even murder. In addition, they may buy or intimidate the electorate to secure votes. In Rio de Janeiro West Zone, in the 2022 elections, investigations by the Federal Police (PF) and the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Rio (MP-RJ) identified at least eight candidates with proven links to criminal organizations.

Influence in political decision-making can give great profits. According to PF’s investigation, this criminal mechanism is behind the assassination of councilwoman Marielle Franco, in 2018. She opposed approving a law proposed by candidates that would be supported by a militia in Rio’s West Zone. The law would regularize reserve land illegally occupied by real state developments built by the militia itself. Similarly, in São Paulo, investigations indicated that the First Capital Command (PCC), a drug-trafficking gang, infiltrated city halls through connections with politicians and public servants to win bids and participate in providing public services, easing the process of money laundering.

Growing Threat in America

Brazil is not isolated in experiencing political violence; many neighboring countries face similar issues driven by deep socioeconomic problems, influential drug gangs, political polarization exacerbated by fake news, widespread armed violence, and populist politicians. Notable examples include Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, and the United States.

On 13 July, during an election rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, former President Donald Trump was targeted in an attack that underscored ongoing polarization and tension in the US. A shooter fired at the stage, killing one spectator and injuring two others. Trump sustained a minor injury to his ear. This incident, along with the Capitol assault and other violent acts, has led some analysts to speculate about a potential new rupture in American politics.

In Mexico, political violence has surged alarmingly. During the last general election, 38 candidates were murdered, including one killed just before the election. These events highlight the troubling influence of drug cartels on Mexican democracy. There were also two voter deaths at voting centers, and voting was halted at an electoral college in Comeyoapan, Puebla, due to a shooting. In Jalisco, security concerns led to the non-installation of five ballot boxes.

Mexican cartels have extended their influence into Ecuador, where they have empowered local gangs responsible for the assassination of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio in August 2023.

Colombia has faced severe electoral violence, significantly impacting its political landscape. Between March and May 2022, the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation recorded 222 victims, including 29 murders and 193 threats. Indepaz reported 42 massacres in 2022 and 1,624 murders of former combatants and community leaders since the Peace Accords. Notably, Senator Paulino Riascos was attacked, and escalating threats against progressive candidates forced the suspension of several campaign activities. These incidents underscore the persistent danger faced by political figures and activists, illustrating the deep-seated challenges to Colombia’s democracy.

Tips for Protecting Yourself from Violence during Elections in Brazil

The official campaign for the 2024 Municipal Elections begins on 16 August. However, candidates are already in pre-campaign mode and can hold events and promote themselves, as long as they do not directly ask for votes. The 2024 Municipal Elections in Brazil will take place throughout the country, except in the Federal District and the Fernando de Noronha archipelago (PE). The first round is scheduled for 6 October, while the second round, if necessary, will be on 27 October in cities with more than 200,000 voters.

Political violence threatens candidates, politicians, and the democratic process itself, moreover, anyone near violent incidents could be harmed or become an unintended target. To mitigate these risks, a list of important recommendations has been prepared to help reduce exposure to danger for both individuals and assets.

- Stay Informed: Keep up with local news and updates on election-related violence in your area.

- Avoid High-Risk Areas:Steer clear of neighborhoods or areas known for violence or militia activity, particularly in cities like Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

- Use Discreet Communication:Be cautious with your communication about political activities and opinions. Avoid discussing sensitive topics in public or on unsecured digital platforms.

- Understand Local Dynamics:Recognize the influence of local militias and criminal factions in your area. Be aware of their activities and avoid interacting with or challenging them directly.

- Avoid Political Associations: Do not wear the Brazilian football jersey or a red shirt, especially near protest zones, as they can be seen as a sign of political affiliation.

- Avoid Crowds and Demonstrations: Steer clear of crowds and demonstrations. If caught in a demonstration, try to leave the crowd quickly, seek shelter in a nearby building, and wait for the demonstrators to disperse. Avoid taking pictures or using your phone.

- Anticipate Security Presence: Expect an increased presence of security forces during the election period.