After two months of protests on federal highways and in front of military facilities, pro-Bolsonaro supporters stormed the three main buildings of the Brazilian administration, in an attempt to oust the newly elected president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. So far, the event was the apex of a movement fueled by the idea, spread mostly through social media, that the last elections were rigged, even though no evidence has been presented. The action seriously damaged the main buildings of the republic and destroyed many national objects of historic and cultural value. However, rioters were unsuccessful in achieving their goal of mobilizing the Armed Forces to back their idea of removing Lula and may have given political stamina to the new government, seen by many as the target of an unlawful attack. Still, after the reports of collaboration from the security forces, it may have also exposed some of the problems that the current administration may face.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

The Attack

On 8 January, thousands of supporters of former President Jair Bolsonaro invaded the Congress, the Federal Supreme Court (STF) and the Presidential Palace (Palácio do Planalto). The rioters overcame the few lines of military policemen and the Army soldiers that were protecting the facilities and vandalized and sacked the buildings.

The main objective of the rioters was to overthrow Lula’s government, who they accuse, without any evidence, of being elected in a fraudulent process. They have been asking for the Armed Forces to carry a military coup.

Most of the rioters that invaded the main facilities of the Brazilian State arrived the day before. Four thousand people were brought in around 100 buses that came from all over the country. The group joined those already camped in front of the Army Headquarters in Brasília.

The preparations for the attack began with messages exchanged between the rioters, who shared through social networks the information that the Military Police officers would be on their side. Hours before the incident, the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (Abin) warned the security forces of Brasília, including the Federal District government, about the risk of invasion of public buildings. Despite that, the acting Secretary of Public Security, Fernando de Sousa Oliveira, told the Governor Ibaneis Rocha that there was no risk of the situation getting out of control.

In the afternoon, around 5,000 people left the site, in front of the Army HQ, towards the Three Powers Plaza. Instead of containing them, the police escorted the group. When the protesters arrived in front of the National Congress, they did not find sufficient resistance, there was only a single barrier with a few policemen who unsuccessfully tried to stop the rioters using pepper spray.

The Congress was quickly taken over by the rioters. They broke windows, destroyed historic furniture and works of art, and damaged virtually every room they managed to access. Authorities believe that many were familiar with the building, since specific rooms with lethal and non-lethal weapons and valuable objects were sacked.

After the Congress, the crowd invaded the Presidential Palace, where the security forces were overwhelmed as well. Destruction and pillage were also seen there. The Federal Supreme Court (STF) was the next target. The cabinet of STF Minister Alexandre de Moraes was particularly targeted. He has been responsible for several cases that have investigated actions supposedly perpetrated by supporters of Jair Bolsonaro. He has also ordered the arrest of many individuals connected to the former President.

According to Senate security forces, there were attempts to convince the invaders to leave, but they remained adamant under the argument that they would only leave dead or when the Army took power. Reinforcements arrived approximately after two hours since the first invasion, and, thus, the buildings were retaken, and people began to be arrested.

In all, 1,843 people were detained, 684 were later released and will respond in freedom. The Federal Police arrested 1,159 people. Still according to the military police, dozens of military police were injured in the clashes.

The damage caused by the acts of vandalism will likely reach R$ 20 million, according to the government. The value does not include the depredation of works of art or the costs of all the recovery of damaged objects. Therefore, the final cost tends to be even greater.

Building Tension

The attack from 8 January was not planned overnight. The context that led to it began to emerge after the second round of the presidential election, when supporters of Bolsonaro started protesting Lula’s victory stimulated by the idea that the election had been rigged. The first sign that the result was not going to be accepted appeared shortly after the official announcement.

On 31 October 2022, trucks belonging to companies and individuals were used to close highways in many states. On 1 November, 421 blockades were reported across 22 states, most in the Southeast and in the South regions, where Bolsonaro received most of his votes. STF Minister Alexandre de Moraes threatened to fine security forces and truck owners if order was not reestablished. After that, the blockades were gradually demobilized, but not without some episodes of intense violence.

Meanwhile, in front of the Army headquarters, in Brasília, the Duque de Caxias Fort, thousands of protesters started gathering to form an encampment to contest the poll results, to pressure the Armed Forces to endorse an intervention, which is unconstitutional. The movement took place on 2 November, and it was replicated in front of hundreds of military bases across the country.

In some cities, the security forces attempted to remove the camps and episodes of violence multiplied. Journalists, seen as part of the opposition, were attacked frequently. More radicalized actions were perpetrated. On 12 December, the day in which President Lula was certified as the winner in a ceremony, hundreds of protesters vandalized the capital, torching buses, and cars, and attacking public buildings, including a police department.

On 24 December, a bomb was discovered in Brasília. The explosive, already activated but not detonated, was found on a fuel truck near Brasília International Airport. The suspects connected to this terrorist attack were in the encampment in the Army headquarters. The first suspect arrested, George Sousa said in a statement to the police that he planned, with demonstrators from the HQ, to install explosives in at least two locations in the capital and “start the chaos” that would lead to the “declaration of a state of siege in the country”, which could “cause the intervention of the Armed Forces”.

The Brazilian “Capitol”

The invasion of the buildings in the Three Powers Plaza, in Brazil, holds many parallels with the invasion of the United States Capitol, which took place in 2021.

The main similarity is the fact that both acts were promoted to contest the elections results. Donald Trump supporters did not accept Joe Biden’s victory, and in Brazil, Bolsonaro’s voters did not accept Lula’s victory. In both cases, the radicals acted violently and there was vandalism. The American and the Brazilian rioters are right-wing and defend conservative agendas. Finally, conspiracy theories and fake news played an important role to provoke both incidents.

However, some differences were noted. In the United States, the target was the Capitol, which is the American legislative center. In Brazil, the buildings of the three powers were invaded. The US Capitol was full of parliamentarians and civil servants, but the buildings in Brasília were empty. In Washington DC, the reaction of the authorities was immediate, in the Brazilian case, videos posted on social networks show police officers just watching the action.

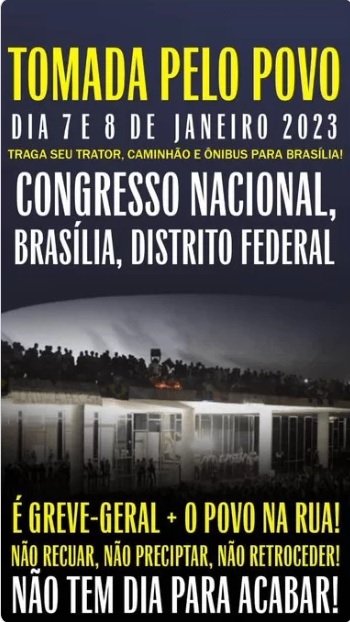

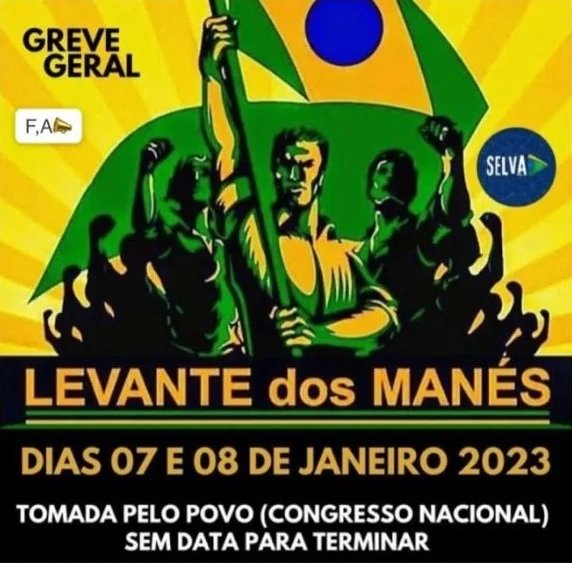

The Call For the Acts

According to political analysts, people involved in the 8 January attack were motivated and organized through a network based on messages shared online via social media and messaging apps, like Telegram and WhatsApp.

This communication network would have spread the idea that the Brazilian electoral system was fraudulent, that the electronic voting machines had been hacked, and thus, that the election was rigged. This perspective would be the main driver for the rioters to block roads with trucks, camp in front of military barracks and, finally, to attack the Three Powers Plaza. This understanding was likely reinforced by statements made by leaders, including former President Bolsonaro, who said many times that previous elections had been rigged and that the electoral system was not reliable.

According to the Federal Police, there are evidence that indicate that the acts of violence and the invasions of 8 January were not just the product of a demonstration that got out of control. Messages collected by investigators suggest that the network would have also been used to organize the event, and they could even represent a premeditated attempt to overthrow the elected government.

For instance, announcements with offers of free transportation to Brasilia were shared on several medias. They show the departure dates of the buses and telephone numbers for contacting the supposed organizers. Buses were offered in São Paulo, in Santa Catarina, in Paraná and other states. The texts also offer militants shelter and food in Brasília.

Funding

The communication system, the transports and the logistics involved in the acts indicate a certain level of organization that suggests some kind of funding. One day after the acts in Brasília, Justice Minister Flávio Dino stated that the government had already identified individuals responsible for giving resources to the demonstrations. People received shelter, food, and transport from sources located in at least ten states, most in Paraná, Mato Grosso do Sul and São Paulo. Later, Minister Dino stated that among the alleged financiers were representatives of agribusiness, merchants, and people with a certificate of hunter, shooter or weapons collector (CACs).

Further work of investigation led the Attorney General’s Office to ask the capital’s Federal Court to block R$ 18.5 million in assets belonging to 52 people and seven companies suspected of funding the rioters that destroyed the buildings in the capital. The amount should be used to repair the damages in case the suspects are convicted.

The Role of the Security Forces

The police and the government of the DF, responsible for security of the Three Powers Plaza, were criticized for their actions in the face of the vandalism promoted by the rioters. President Lula declared that the police officers who took part in the incident will not stay unpunished, nor will remain in the corporation. Images made by reporters and bystanders show officers taking pictures and chatting while rioters attacked the facilities. In addition, videos posted on social media show what appears to be some policemen colluding with rioters.

Other videos show that Brazilian Army soldiers may have also hampered the protection of the buildings. The commander of the Army’s Presidential Guard Battalion, Colonel Paulo Jorge Fernandes da Hora, was seen arguing with agents of the PM-DF riot police while rioters vandalized the Congress. The officer, responsible for escorting President Lula (PT) and protecting the presidential palaces, is accused of disrupting the police actions. Testimonies made to the police by arrested demonstrators indicate that the Army members tried to help rioters to avoid arrest. One of the prisoners stated that “an Army commander told the demonstrators to use an emergency exit, inviting them to leave (…)”.

Specialists, such as former DF Security Secretary and Universidade de Brasília (UnB) professor, Artur Trindade, also believe that everything was totally out of the expected protocol. He said that the size of the protest and the degree of risk demanded a different response.

In addition, members of the security forces were seen taking part in the protest. So far, at least 15 have been identified. Among these, there is an Army reserve general, Ridauto Fernandes, an Army colonel, Adriano Camargo Testoni, and a Navy Captain, Vilmar Fortuna. This helped spread more distrust between the government and the security forces.

Previous Cases

However, this is not the first time that the security forces’ behavior is put into question by political leaders. Many other episodes of similar nature have been feeding distrust between members of the new government and those that are tasked with protecting the Brazilian institutions.

During the elections’ second round, on 30 October, the Federal Highway Police (PRF)) set a series of check points that would have stopped and delayed voters, making it harder for them to arrive at their voting zones. The actions were carried out mainly in the Northeast region, where historically most of the population votes for Lula. Critics said that it was a violation of the right to vote. On the following day, when truckers began closing highways throughout the country to protest Lula’s victory, the PRF was also accused of being lenient with demonstrators and, in some cases, even showing support for their cause. The institution’s Director at that time, Silvinei Vasques, ended up being investigated for both events. Suspicions about him increased due to his connections with Senator Flávio Bolsonaro, son of the former President.

Amid the proliferation of encampments in front of military barracks, with protesters demanding a coup, on 11 November, the Brazilian Armed Forces released a letter to condemn what they classify as “possible restrictions on the rights” of those who criticize public agents. Signed by the forces commanders, Admiral Almir Garnier Santos (Navy); by General Marco Antônio Freire Gomes (Army) and Lieutenant-Brigadier Carlos de Almeida Baptista Júnior (Airforce), the document was seen by political commentators as a way to covertly criticize Supreme Court (STF) orders that determined the removal of the camps.

Response

On the same day of the attack, authorities began announcing measures to investigate and punish people responsible. Anderson Torres, who had recently been placed as Federal District Security Secretary, was sacked from his position, and arrested under the order of STF Minister Moraes. His subordinate, Colonel Fábio Augusto, who commanded the police, was arrested as well. Minister Moraes explained his decision saying that the Federal Police, which investigates the attacks, pointed out several omissions, in thesis malicious, practiced by those responsible for the public security in the capital. Federal District Governor Ibaneis Rocha, responsible for appointing the security secretary, was removed from office for 90 days.

The President said he was convinced that both the police and the Army were colluding with terrorists and that someone allowed them to enter the Presidential Palace. After demonstrating distrust with the military who work in the government, he signed an intervention decree to take control of public security in the Federal District, which was later approved by the Congress. More than 40 members of the Armed Forces who worked at Presidential Palace and personnel from the Institutional Security Office (GSI) – who work in the Coordination of Presidential Security – were dismissed too. Media sources also reported that the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (Abin), which is currently subordinated to the GSI, will be moved away from the influence of the Armed Forces, and placed under the Chief of Staff of the Presidency.

The most important change in command caused by the incident was the removal of Army Commander, General Júlio César de Arruda. In addition to the series of security problems in which the Army appears to be involved, a few other factors led to his removal. First, Arruda’s decision to prevent the police to access, on the day of the attack, the rioters’ camp in front of the Army HQ, in Brasília. He placed armored cars and soldiers to prevent the arrests, which may have allowed protesters to escape. Second, the fact that he refused to comply with Lula’s order not to give the command of the Special Forces Army Battalion in Goiânia, a strategic unit, to a close ally of Bolsonaro, Lieutenant Colonel Mauro Cesar Barbosa Cid.

The events of 8 January represented, so far, the apex of a growing crisis between the new government and the country’s security forces. Thus, according to analysts, it prompted authorities from the capital to give attention to other institutions that did not have a direct agency over the attacks but were involved in other incidents. Some of the consequences were the removal of 26 of the 27 regional directors of the PRF in the states and in the Federal District, and the change of Federal Police directors in 18 states.

The Impacts on the New Government

For the experts, in the end, the attacks in Brasília strengthened the new government in the country and around the globe. Locally, it showed capacity to articulate a quick and organized response. Internationally, a great support was shown through declarations of important global leaders from different political spectrums. For instance, US President Joe Biden called the event “outrageous”. The Kremlin condemned the invasion and said it “fully supports” President Lula. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement stating that it “firmly opposes the violent attack” against the seats of power in Brazil.

On the other hand, the incident probably exposed the serious consequences that the bad relation between the security forces and the government can cause to the country’s stability. The new commander of the Army, General Tomás Paiva, took office with the delicate mission of pacifying the relationship between Lula’s government and the Armed Forces. Two topics, however, are already emerging as new points of tension that the general will face right away: pressure to punish military involved with the acts of 8 January and where their trial will take place.

Gen. Paiva has defended that the military involved with the invasion be exemplarily punished. He even declared that nobody is above the law, military or civilian. However, high-ranking members of the three forces, in particular, the Army, defend that the trial takes place before Military Courts. But the Federal Supreme Court (STF) disagrees. Most judges believe that the STF is the forum where the military involved in the attacks should be prosecuted.

On 13 January, STF Minister A. Moraes accepted a request from the Attorney General’s Office (PGR) to include former President Bolsonaro in the inquiry that investigates the intellectual authorship of the acts. The decision is another point of tension developing from the incident that can affect the new government, because it could lead to the arrest of the former president, hence, fueling new riots. Local media sources have disclosed that this perspective is shared by ministers of the Federal Supreme Court (STF). They assess that today it would be a “mistake” to determine his arrest, since it could further disrupt the national scene, whether in the social or political sphere. The judges say that this scenario, however, may change if the former president acts directly to inflate new actions against the Brazilian democracy.

In addition to the arrests and dismissals already carried out to punish those that may be connected to the attacks, the government is also planning a package of measures to reduce the chances of future incidents. Justice and Public Security Minister Flávio Dino presented a first draft of this document to President Lula. The main proposals involve creating a police force to protect federal agencies; drafting of a bill to punish sponsors of coup demonstrations; and the launch of tools to “moderate” content considered extremist on social networks. Some of the proposals need to be submitted to Congress. Nonetheless, Dino plans to take advantage of the still latent commotion of parliamentarians with the scenes of destruction in the Chamber and Senate to approve them quickly.