Summary

The upcoming COP30 in Belém, Pará, presents a complex security environment shaped by the city’s high rates of property crime, the presence of organized criminal factions, and limited urban infrastructure. While large-scale terrorism is unlikely, threats such as petty theft, fraud, and opportunistic attacks against visitors remain elevated, particularly outside the main event zones.

Beyond Belém’s existing crime challenges, international guests face specific, heightened risks. These dangers can be broadly categorized into activities that invite criminality—such as the temptation to use illicit drugs or engage in commercial sex/prostitution, especially with minors—and the risk of GHB-facilitated assault (rape and theft) or suffering catastrophic harm from consuming Methanol-Laced Distilled Alcohol.

Maritime piracy in nearby waterways, flooding during heavy rains, and cybercrime add additional layers of risk. Authorities have planned an extensive security operation involving 10,000 personnel from multiple agencies and the UN, supported by new infrastructure and three concentric security zones around the main venue, Parque da Cidade. This layered protection aims to ensure safety within the official perimeter, though risks will increase sharply for those engaging in tourism or lodging in outlying areas.

Operational stressors extend beyond security: Belém’s limited accommodation capacity, logistical bottlenecks, and tropical climate create mobility, health, and safety challenges. The lodging shortage may push attendees into unsafe neighborhoods or expose them to scams, while the city’s flooding-prone streets can disrupt mobility and emergency responses. Visitors are advised to maintain strong cyber and physical security protocols, use pre-screened transportation, avoid public transit and high-risk areas, and ensure vaccination against yellow fever and other diseases. With careful coordination, robust communication, and adherence to security guidelines, Brazil’s combined federal and UN-led framework can likely contain most operational threats during COP30, though residual risks will remain for off-site movements and civil demonstrations.

COPs’ Security Risks

United Nations Climate Change Conferences (COPs) concentrate heads of state, negotiators, CEOs, activists, scientists, and media in a single, time-boxed venue that is both a diplomatic summit and a mass-participation civic event. This hybrid nature creates a distinct, recurring risk profile that conventional summit security playbooks do not fully cover.

Across editions, risks have clustered around three fronts: terrorism; espionage and cybercrime; political activism, protests, and repressive surveillance. Past incidents show how each front can disrupt negotiations, chill participation, or erode trust.

Terrorism

The most notorious episode of terrorism connected to a COP took place in 2015, in Paris, during the 21st edition of the conference. Just two weeks before the event, on 13 November, seven individuals connected to the Islamic State (IS) carried out attacks with firearms and explosives, killing 130 people. Authorities declared a nationwide state of emergency, banned mass marches and hardened perimeters, prioritizing the protection of dignitaries and venues over street mobilization. Many activists considered this a suppression of the right to protest.

Brazil has occasionally encountered security challenges related to international terror groups. Individuals with ties to organizations like ISIS, Hamas, and Hezbollah have been detained within the country over the past decade. The most significant moment of tension occurred just before the 2016 Olympic Games, when the Federal Police arrested a jihadist cell allegedly planning attacks during the event. Despite these incidents, Brazil is generally not considered a primary target for terrorism, and the overall risk of attacks remains low.

Espionage and Cybercrimes

COPs attract state-level espionage and opportunistic hackers. The 2009 “Climategate” leak of researchers’ emails landed weeks before COP15. The emails were used to claim that scientists were exaggerating the threat of climate change, damaging trust in negotiations. During the same edition, it was discovered that the United States used the National Security Agency (NSA) to spy on other countries. In COP19, COP21, and COP27, there were reports of cyberespionage by governments to steal documents and gain advantages to negotiate with delegations and NGOs.

Credential or data exposures have also been reported. In COP21, the hacker group Anonymous stole and disclosed names, logins, phone numbers, and email addresses of 1,415 individuals from several countries, including the United Kingdom, France, Peru, and Switzerland.

Brazil has been one of the main targets of cybercrimes of all kinds and on different scales, affecting companies, common users, the government, and visitors. On 1 July, the Brazilian instant payment system (PIX) was hacked, leading to a loss of almost BRL 1 billion. Another one, in August, stole BRL 710 million. The incidents show that this is a major risk. Therefore, attendees must come with a strong and tailored cybersecurity protocol.

Political Activism, Protests, and Repressive Surveillance

Protests are an integral part of events like the COPs. Large demonstrations and occasional confrontations outside and inside the event’s premises have taken place. Cases of protests within COP facilities were seen in COP19 and COP25. In the first, there was a large “walkout” of NGOs protesting the process, although non-violent, it required security/access management. In the second, after a protest inside the site, observers were removed, “debadged”.

However, the biggest disturbances happen outside. COP15 had many protests, with around 40,000 to 100,000 people marching, and in some cases, facing the police in violent episodes. Detentions reached almost 1,000. COP26 also had large protests, although generally contained; there were moments of tension and confrontation between police and protesters who tried to block roads and access to the convention center.

In this sense, in Belém, the challenge lies in the balance between crowd management to protect peaceful protests and measures to prevent escalation. Brazil has a history of large protests, especially in big urban areas. Moreover, the North is a focal region for environmental NGOs and other groups, like the Landless Workers Movement (MST), the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB), and indigenous people. In addition, after years of curtailed protest in host countries with tight controls – COP27 Egypt, COP28 UAE, COP29 Azerbaijan –, civil society expects the “streets” to be open for acts. A set of 100 NGOs has even written a letter to request the organization to grant the freedom to protest and the inclusion of activists and civil society. Meanwhile, the UNFCCC has warned of an acute lodging squeeze and asked its own agencies to shrink delegations, an operational stressor with knock-on security effects.

Belém’s Security Risks

Belém has markedly reduced lethal violence in recent years. Official data show homicides falling from 877 (2017) to 213 (2024). Nonetheless, the city’s homicide rate for 2024 still indicates a violent environment, with 16.3 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, mostly related to gang disputes.

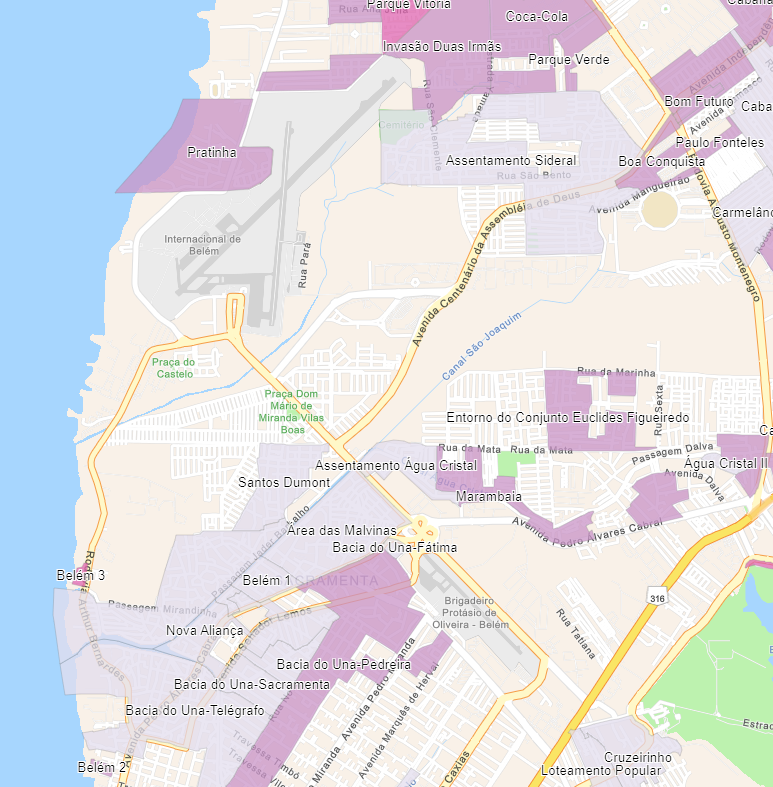

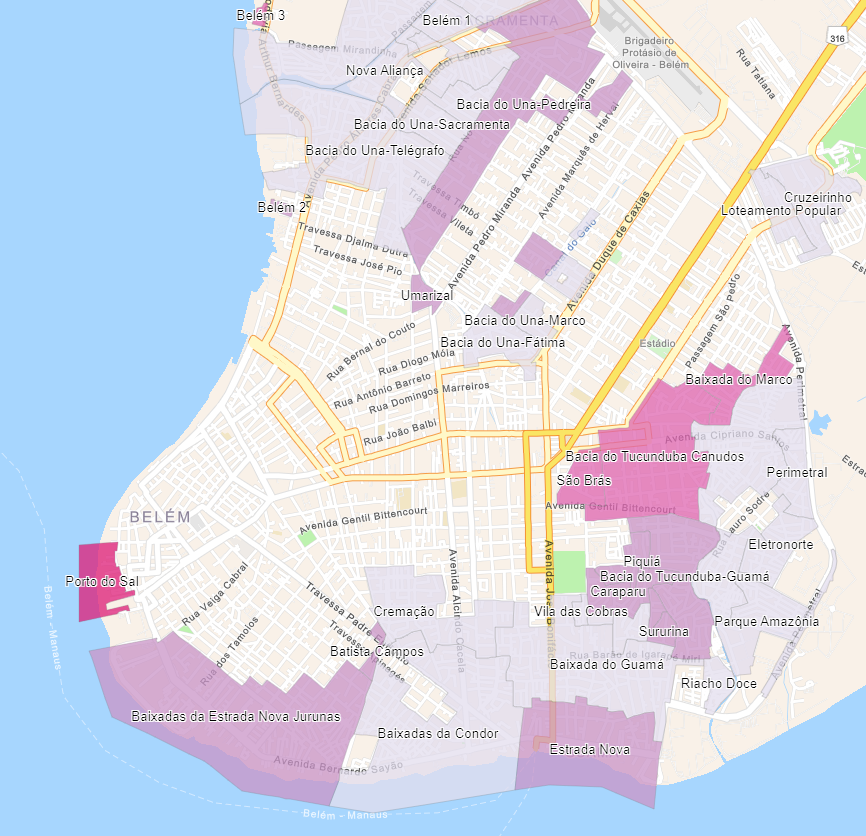

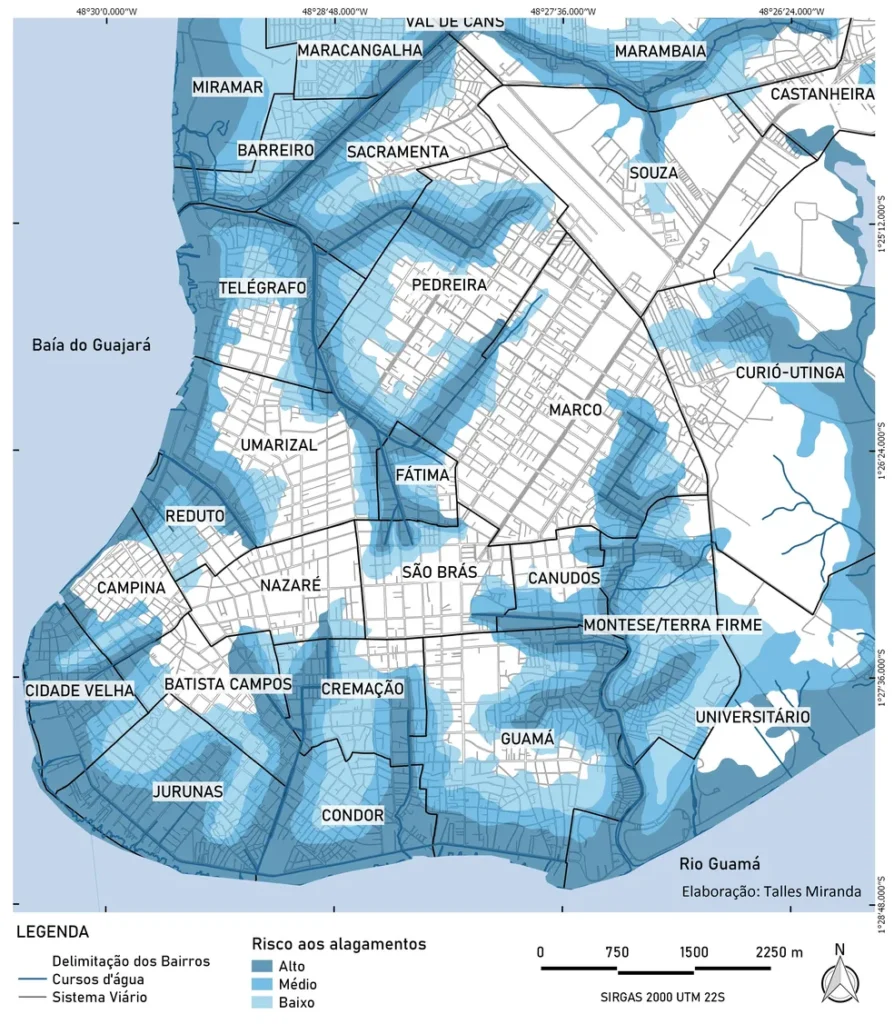

The neighborhoods where the airport and the COP30 site are located, respectively, Aeroporto and Souza, are not among the dangerous locations, with relatively low numbers of crimes reported yearly. However, both are surrounded by neighborhoods with bad security conditions. Around Souza, there are Marco and Curió-Utinga, and in the surroundings of Aeroporto, some parts of Maracangalha and Sacramenta, near Av. Júlio César and Av. Pedro Álvares Cabral.

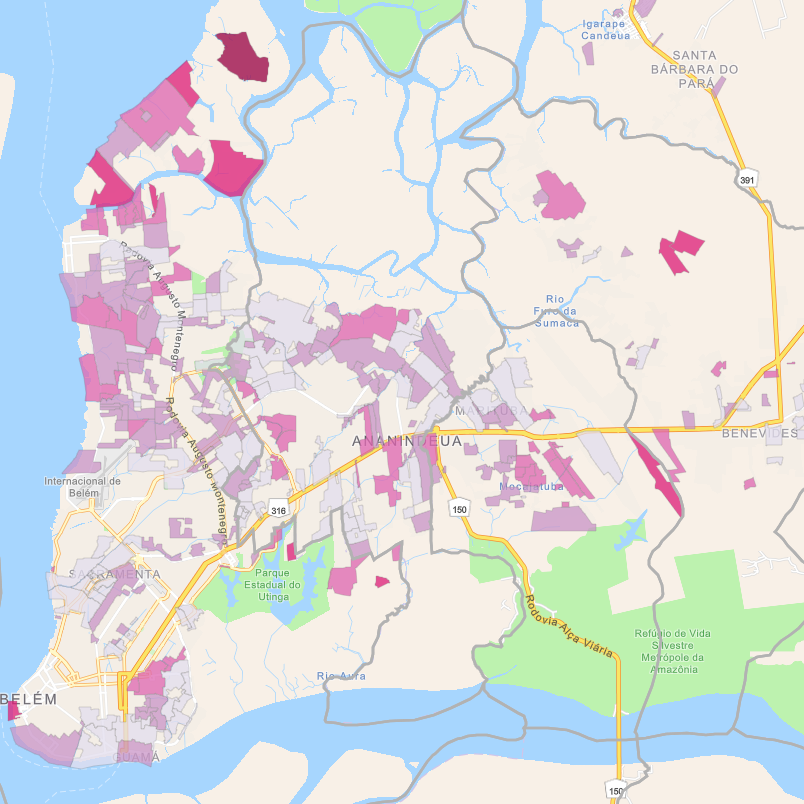

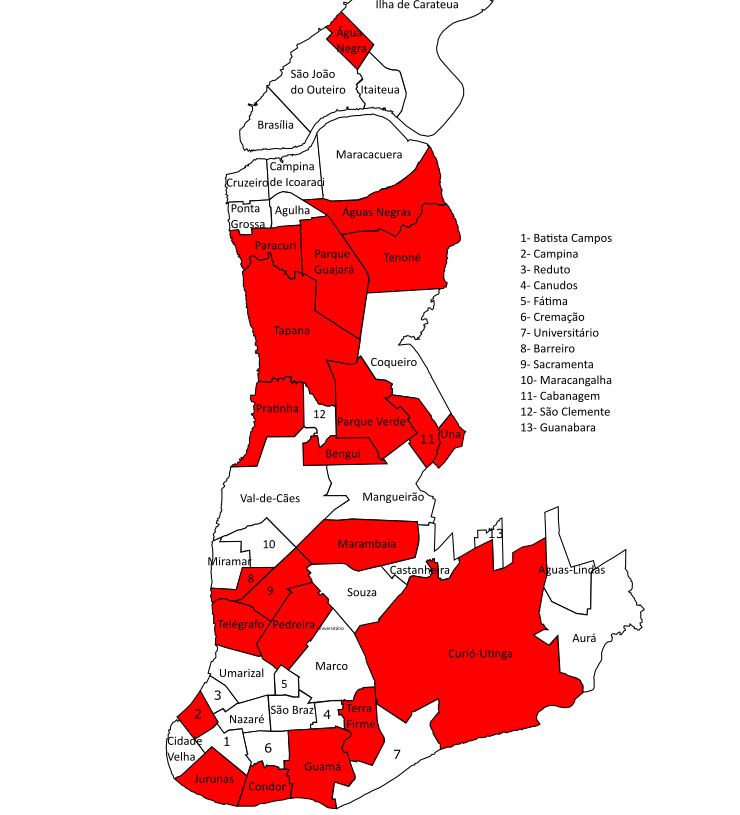

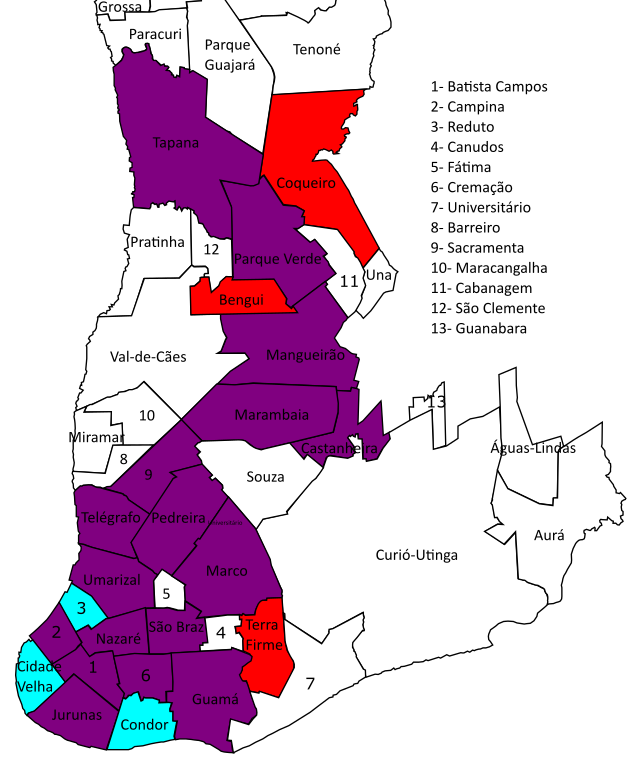

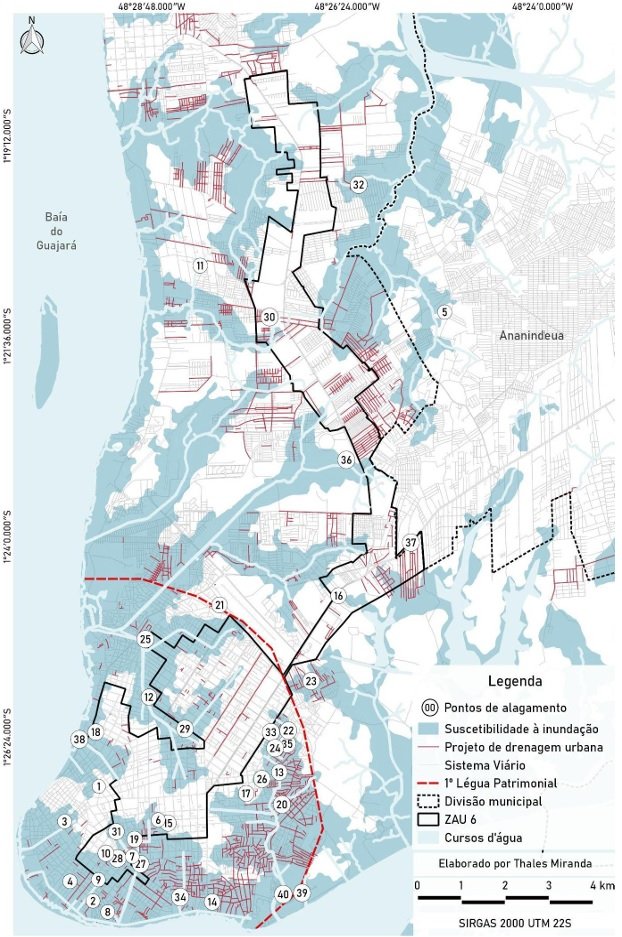

The country’s second most powerful faction, Red Command (CV), is the predominant organized crime power in the Metropolitan area. It shares informal control of vulnerable neighborhoods with other local groups; some are allies, while others are rivals. When it comes to organized crime hotspots, the main ones are: Guamá, Terra Firme, Sacramenta, Pedreira, Condor, Parque Verde, Marambaia, Telégrafo, Tapanã, Jurunas, Cabanagem, Campina de Icoaraci, Paracuri, Pratinha, Benguí, Una, Águas Negras, Barreiro, Tenoné, Parque Guajará, and Curió-Utinga.

Property crime remains the most common risk for travelers; thefts represent almost 50% of the crimes committed in the city since 2021, but robberies are also significant, around 39%. In 2024, Belém was the city with the second-highest rate of cell phone theft and robbery, 1,452 for every 100,000 inhabitants. Most thefts are committed from 8h to 12h and from 17h to 20h. Meanwhile, most robberies occur in three different periods: from 5h to 7h, from 12h to 14h, and from 18h to 22h.

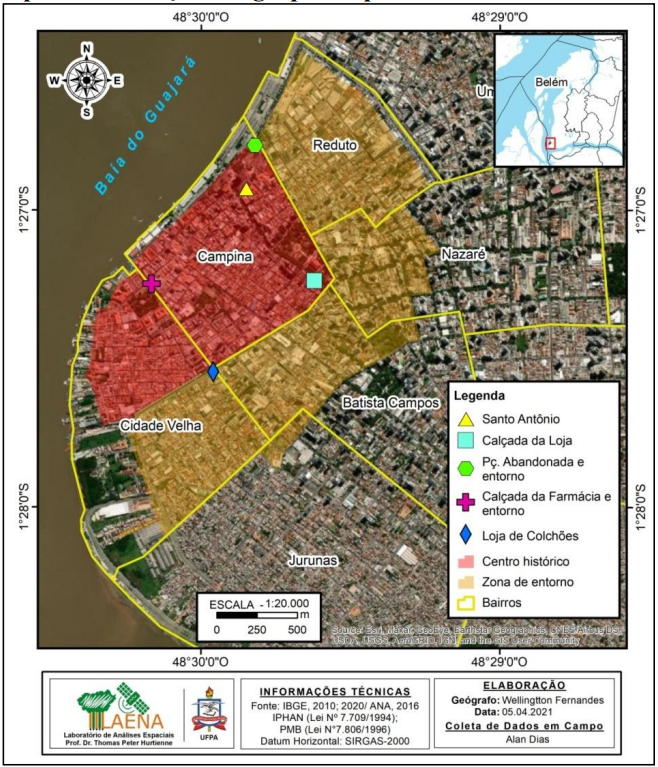

Street robberies and phone snatches occur on high-flow corridors, commercial strips, bus terminals, and crowded hubs. Pickpocketing is reported in the old town and the Ver-o-Peso Market, where tourists and visibly affluent visitors are targeted.

Many neighborhoods have narrow streets, and some are poorly lit, affected by bad sanitation and drainage, making the action of robbers and thieves easier, and any escape from risky situations by car or on foot much more difficult.

Central areas are also occupied by groups of addicts, the famous “cracolândias”, where petty crimes are common. These locations are normally found spread across the neighborhoods of Cidade Velha, Campina, and Reduto.

Travelers must remain vigilant about the increasing number of scams and frauds nationwide. From 2018 to 2024, such crimes increased by 407%. As people attending COP30 will remain in the country for a very short period, opportunities for scams may arise when paying for something or using a local service. To reduce risk, be wary of credit card machines with broken screens, and check data before completing the payment.

Nightlife and Underworld Risks

Foreign visitors coming to Belém for the event may be tragically drawn into activities that put them into direct contact with organized crime networks. The foreigner can be attracted to take the opportunity of consuming illicit drugs, especially cocaine, which immediately links them to potential criminal offenses and creates significant health problems. Similarly, seeking prostitution services links people to groups profiting from human trafficking and exploitation. All these activities imply a direct, dangerous, and high-stakes relationship with organized crime, exposing the visitor to legal peril and violence.

International visitors also face the serious risk of assaults due to GHB (Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate), which is increasingly used by criminals to facilitate rape and theft. This potent “date-rape” drug can lead to incapacitation, leaving the victim vulnerable to both personal attack and robbery, while also causing severe, acute health problems like respiratory failure.

Furthermore, a widespread and critical public health danger exists due to the presence of Methanol-Laced Distilled Alcohol on the market. While early cases were concentrated in São Paulo, the illicit market that supplies this contaminated liquor operates nationally. Unwittingly consuming this toxic substance can lead to catastrophic health problems, including permanent blindness, organ failure, and death. It is recommended to avoid distilled spirits and choose sealed beer, bottled soft drinks, or wine.

Maritime Piracy

Belém offers attractive tourist experiences across many islands in the surrounding rivers. However, these trips are not free of risks. The local waterways are plagued by pirates, commonly called “water rats”. They operate in small, fast boats, use firearms, machetes, and even homemade explosives. Although their primary targets are commercial shipments, personal belongings are also stolen. Many pirates are well-organized and work with informants in ports and river hubs, allowing them to identify high-value targets. Attacks frequently occur at night and in isolated river sections, especially on Thursdays and Fridays.

The Event’s Organization

The 30th edition of the United Nations Climate Change Conference will likely attract a public of around 50,000 visitors, including around 190 heads of state, diplomatic delegations, private sector representatives, activists, journalists, NGOs, indigenous peoples, and academics. From 6 to 7 November, during the Leaders’ Summit, and from 10 to 21 November, during the general event, they will meet in the event’s venue, Parque da Cidade, in the Souza neighborhood.

The city’s urban infrastructure and level of services, which are much inferior to those of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, and its lack of history of hosting international events, present numerous challenges in sectors such as accommodation and logistics, thereby increasing exposure to local risks. However, the Federal Government has been trying to fill the gaps, assisting with experienced personnel – who have experience with the 2016 Olympics, the G20, and the BRICS summits – and resources, around BRL 4,7 billion. Furthermore, a strong security scheme was prepared, and many public works have been started to improve local conditions.

The Main Venue and the Security Measures

The newly built Parque da Cidade will be the main stage of the COP30. The facility was divided into two parts: the Blue Zone and the Green Zone.

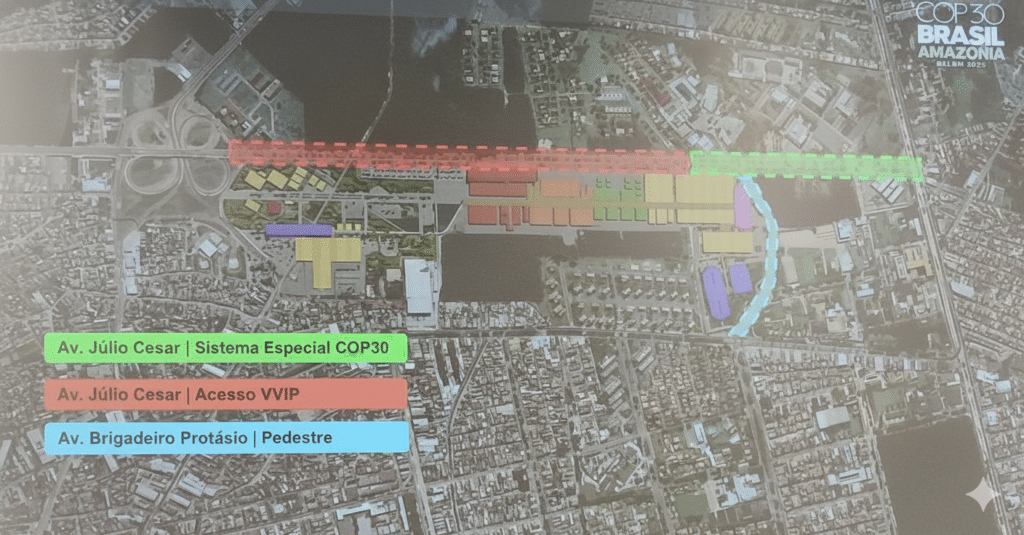

The Blue Zone is the primary venue for official negotiations, the Leaders’ Summit, and national pavilions. Only accredited attendees will be allowed to enter. It will remain under the jurisdiction of the UN Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS). Access control will include credential confirmation and screenings at access points.

The Green Zone is the space where civil society, public and private institutions, and global leaders will be able to meet. In this zone, under the Brazilian Presidency’s responsibility, security measures will also be reinforced. A ticket will be necessary to enter.

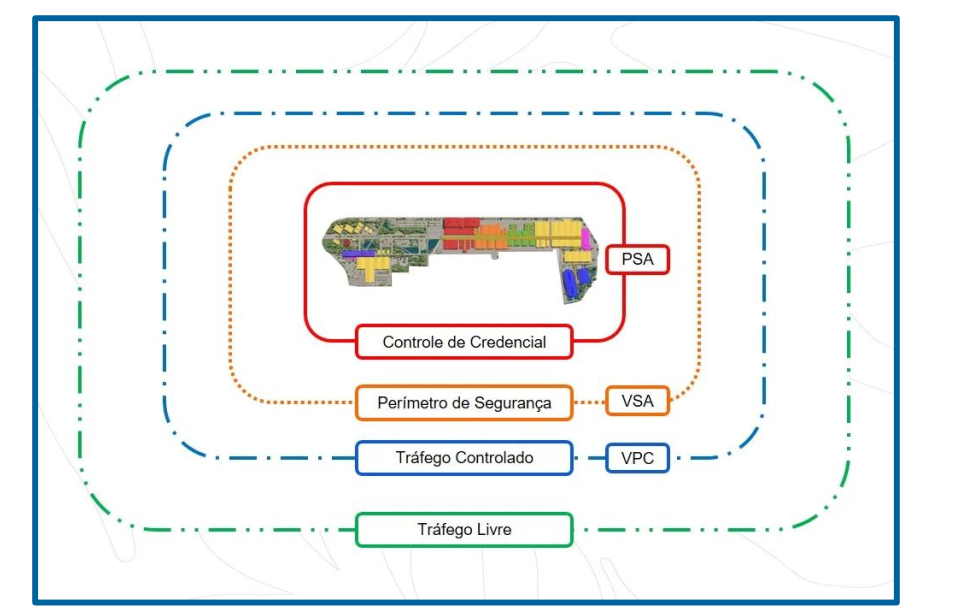

The Parque da Cidade will be protected by layers of security. Three security zones were set around it. The first layer is the Controlled Traffic Zone (VPC), where there will be vehicle permit checkpoints, and only authorized vehicles will be able to enter. The second layer is the Security Perimeter Zone (VSA), where only vehicles that were screened by security will enter. The third layer is the Credential Control Zone (PSA), where people will be screened to be allowed to enter.

The security zones are part of a large-scale security plan that has been developed by Brazil and approved by the UN. The document was structured around four main axes: security of authorities, security of events, protection of critical infrastructure, and cybersecurity.

Operations’ control will be centralized in an ICCC, where institutions will have representatives. The ICCC will also receive emergency calls through the Brazilian 190 emergency number or their Asia, US, and European equivalents, 911 and 112. Service in multiple languages will be available.

To execute the security plan, approximately 10,000 men from the Army, Air Force, Navy, Military Police (PM), Civil Police (PC), Military Firemen (BM), Federal Police (PF), Federal Highway Police (PRF), Municipal Guard (GM), Brazilian Intelligence Agency (ABIN), and UN security forces (UNDSS), will be mobilized. Strategic locations will receive particular attention, the airport, Parque da Cidade, highway BR-316, Porto do Outeiro, downtown Belém, and the local waterways.

Protection around and inside the main areas of the event should significantly reduce risks. Moreover, security forces have been carrying out operations across the city to repress organized crime, and they should not represent a big issue, preferring to maintain a “low profile”. The biggest threats are likely at any attempt by visitors to leave the areas of the event to do tourism or leisure activities, becoming great targets for property and personal crimes detailed hereabove.

Accommodation

Despite the 53,000 beds across 28,000 rooms available to rent in the city, accommodating all the visitors has been an issue in Belém, due to a shortage of rooms and a surge in prices. In August, 25 countries delivered a letter to the UN Secretariat, warning about the risk of exclusion.

In response, the Extraordinary Secretariat for COP30 (Secop) informed that measures were taken to resolve the issue, and that approximately 2,500 rooms have been reserved for the 196 Parties of the Convention on the official accommodation platform. There are offers of up to 15 rooms each, priced between US$100 and US$200, for countries with fewer resources. The remaining countries were guaranteed 10 rooms per delegation, with rates between US$200 and US$600. Among the available rooms, 3,900 are in two cruise ships that will remain in Porto do Outeiro. In addition, the general public should benefit from a Justice decision, from 3 October, to fine online booking platforms – Booking, Agoda, etc. – for abusive prices.

The issue of accommodation potentially increases the security risks by forcing participants to accept rooms in less safe areas and/or more distant, such as Outeiro, which is 20 km away from the main venue. Before renting, visitors should preferably evaluate the security of the neighborhood where the accommodation is located, the security of the routes to Parque da Cidade and the airport, and even if the accommodation exists, since there is the risk of a scam. Having someone to assess risks locally is the best solution.

Mobility

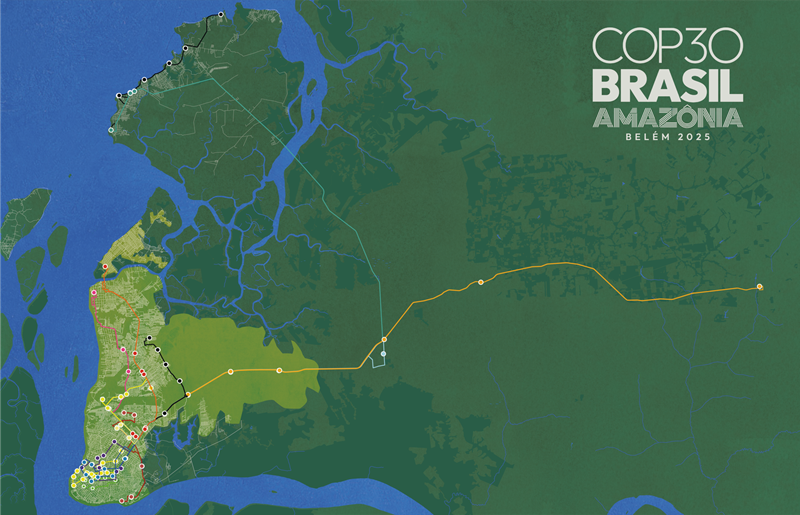

Most visitors will arrive in Belém at the Belém International Airport (BEL), which is in Aeroporto neighborhood, around 4 kilometers from the Parque da Cidade, a 15-minute trip. Some foreign nationals will be required to obtain a visa. Those already accredited for COP30, will have access to an e-Visa.

Besides BEL, there are other options of airfields where small private planes doing national flights can land. One is found in Benevides, 30 km from the event location, a 45-minute trip. Another one is in Castanhal, 69 km from the main venue, 1 hour and 20 minutes by car.

Emergency/evacuation plans should consider these airfields, as well as the fundamental role of BR-316 to reach them, and as the only main highway out of Belém. In this sense, waterways in the local rivers should also be considered.

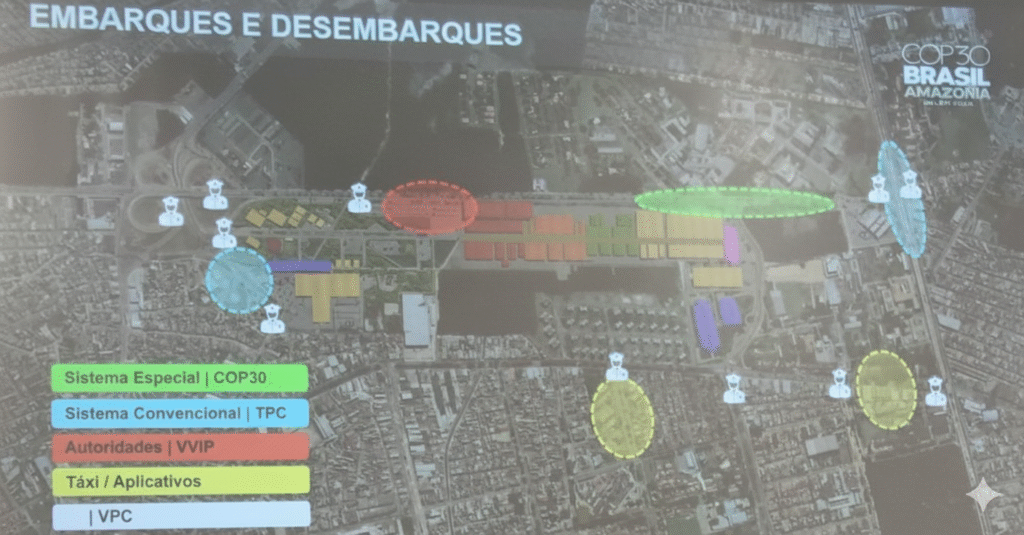

In Belém, to guarantee transport to people attending the COP, an exclusive system of 15 bus routes was created for accredited participants. Locations like the Porto do Outeiro will have buses operating 24 hours a day, from 01 to 23 November. To access the stops, which will be signposted, participants must present their Blue Zone accreditation or a letter from the UNFCCC.

Taxis and ride apps will be available. Participants using the taxi service must board/disembark on Av. Visconde de Inhaúma. Mobility via app-based cars will be provided in an exclusive area on Av. Rômulo Maiorana. For the general public, there will be no parking at the event venue. Parking will be very limited, and preference will be given to heads of state, UN personnel, and official delegations. If attendees use a private vehicle, boarding and disembarking will be on Duque de Caxias Avenue.

In Parque da Cidade, security will set access zones. Delegates, media personnel, and other participants must apply for vehicle permits in advance if they require access to restricted areas. To access these zones, vehicles and people will undergo security screening.

The use of public transportation, taxis, and ride apps is not advised due to the high exposure. Delegations should hire bulletproof vehicles and vetted drivers. In order to acquire such services, due to availability and price, attendees should strongly consider service providers from other parts of Brazil.

Due to the expected increase in traffic, participants are advised to seek accommodation as close to the venue as possible and plan their daily trips carefully.

Weather

The weather in Belém during November is hot and humid. Temperatures range from 24°C to 32°C. Even though this is a drier period, there can be heavy rains in the afternoon, leading to flooding in areas most prone to this issue, disrupting traffic and energy supply.

Belém is located in a riverside region, close to major waterways and the mouths of Amazonian rivers, and it is also influenced by the tides. During high tides, the drainage capacity of the canals is reduced, favoring the flooding of low-lying or poorly drained areas.

Health and Food

Before coming to Belém, it is recommended to get vaccinated against yellow fever 10 days before travel. It is also worth checking vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, measles (combined with mumps and rubella), hepatitis B, among others.

Even though Brazil has a universal public health system – with emergency (192) -, and on-site medical services will be provided in the Parque da Cidade; it is recommended to hire a health insurance that gives access to the best local hospitals, such as: Beneficiência Portuguesa and Porto Dias.

Visitors must be careful while eating out, prefer food that has been cooked, and should not drink tap water. It is important to only drink bottled water and avoid ordering ice with your beverage. Tap water is not sufficiently treated, and it can carry many diseases.

Accommodation with mosquito screens or air conditioning systems are important to avoid mosquito-borne diseases, like Dengue and Malaria. Other great measures include wearing long-sleeved clothing and repellents.