Summary

Brazil is facing an increasingly severe crisis of gender-based violence, marked by rising feminicide rates, escalating brutality, and the expansion of risk across public and private spaces for women. National data show record levels of feminicide in recent years, placing the country among those with the highest numbers of gender-motivated killings worldwide. High-profile cases have shocked public opinion and reinforced the understanding that violence against women is systemic rather than exceptional. In response to this environment, individual safety measures have gained visibility as responses to persistent risk, reflecting both the urgency of protection and the limits of individual self-defense. Researchers and international organizations describe the situation as an epidemic of gender-based violence, reinforcing that personal precautions alone cannot substitute for effective prevention, institutional protection, and collective responsibility in safeguarding women’s lives.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

Escalation of violence and recent cases

Recent cases across Brazil illustrate not only the growth in the number of feminicides and attempted feminicides, but also an alarming escalation in their brutality and diversity of contexts. In December, the death of Henay Rosa Gonçalves Amorim, 31, initially treated as a traffic accident on the MG-050 highway, was reclassified as feminicide after the attentiveness of a tollbooth worker raised suspicions. The employee noticed unusual behavior from Henay’s boyfriend and the woman’s motionless body in the driver’s seat. The investigation later confirmed that her partner had deliberately caused the crash to simulate an accident.

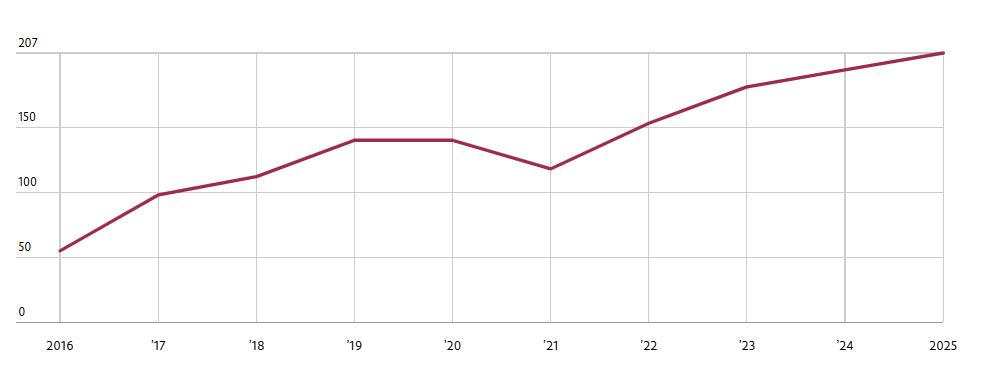

In São Paulo, violence has intensified in both frequency and severity. In late November, Tainara Souza Santos, 31, was run over and dragged for nearly one kilometer after leaving a bar in the city’s north zone. Days later, another woman was shot multiple times by her ex-partner at the pastry shop where she worked. Both cases were registered as attempted feminicide, with Tainara losing both legs and remaining hospitalized. By November 2025, São Paulo’s capital had recorded 53 feminicides—the highest number in its historical series—representing a 23% increase compared to the same period in 2024 and a staggering 71% rise compared to 2023.

Beyond domestic or intimate settings, other cases emphasize risks faced by women in public spaces. Catarina, a graduate student at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, was raped and murdered while heading to a swimming class. Similar patterns appear in the deaths of Bruna Oliveira, killed on her way home from the subway, and Julia Rosenberg, murdered during a walk on a trail considered safe. According to UN data, most gender-motivated killings are committed by people close to the victim, but these sexual feminicides—combining sexual violence and murder—reveal an even broader spectrum of threats.

Together, these cases show that lethal violence against women is expanding across settings and relationships, paving the way to examine forms of gender violence that extend far beyond homicide itself.

Violence beyond homicides

Murder represents the most extreme outcome of gender-based violence, but recent data make clear that lethal crimes are only the endpoint of a much broader and persistent pattern of abuse. According to the fifth edition of the study “Visible and Invisible: The Victimization of Women in Brazil”, released by the Brazilian Forum on Public Security, 37.5% of Brazilian women reported experiencing some form of violence in the past 12 months—the highest level recorded in the survey’s historical series. This percentage corresponds to an estimated 21.4 million women aged 16 or older.

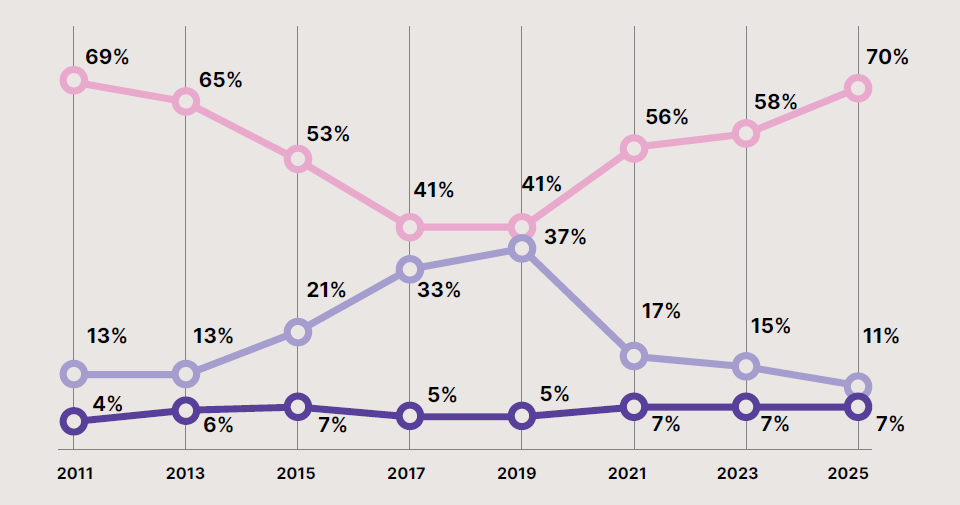

Other severe forms of violence are also widespread. 7.8% of women reported beatings or attempted strangulation, while 6.4% were threatened with knives or firearms, and 8.9% were injured by objects thrown at them.

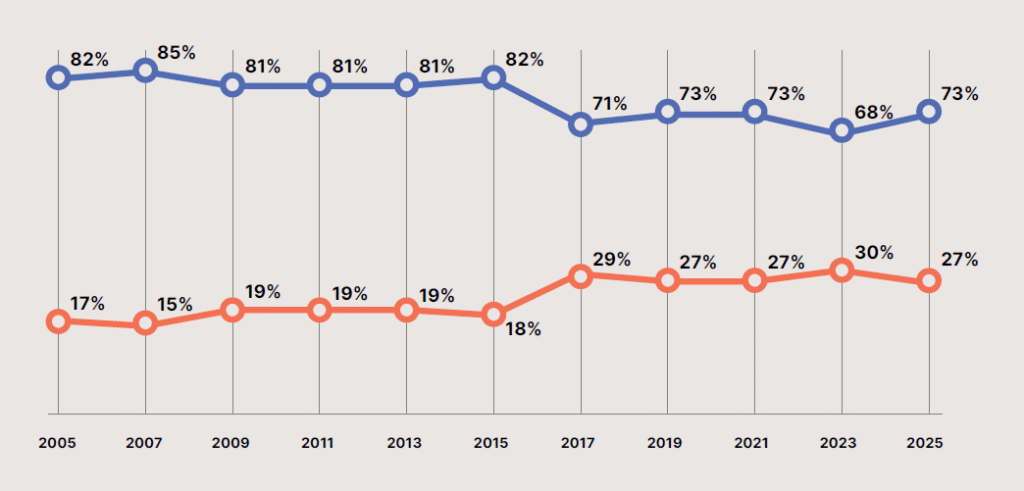

The prevalence of sexual violence is particularly alarming. 10.7% of women—approximately 5.3 million—reported sexual abuse or being forced to engage in sexual activity against their will. Verbal violence remains the most common form of abuse, affecting 31.4% of women, or about 17.7 million, through insults, humiliation, and verbal attacks. Physical aggression was reported by 16.9% of respondents, equivalent to 8.9 million women, the highest rate since 2017. Other recurring forms of violence include threats of physical aggression (16.1%, or 8.5 million women), stalking[1] (16.1%, also affecting 8.5 million), and digital violence while 3.9% of women—around 1.5 million—had intimate photos or videos shared online without consent.

Violence often occurs in front of witnesses: 91.8% of victims said the episodes happened in the presence of others, including children (27%) and friends or acquaintances (47.3%). The home remains the most dangerous place, with 57% of the most severe incidents occurring in the victim’s residence, and intimate or former partners accounting for the majority of aggressors.

Importantly, gender-based violence extends into professional life. In this context, 20.5% of women reported experiencing harassment in the workplace, demonstrating that employment does not shield women from abuse. These statistics reinforce that feminicide is rarely an isolated act—it is typically the culmination of prolonged, repeated, and normalized violence across multiple spheres of daily life.

Self-Defense Practical Limits

Against the backdrop of widespread and recurrent gender-based violence, personal defense tools have gained visibility as part of everyday safety strategies for women in Brazil. This growing reliance on individual protective measures reflects not empowerment alone, but a constrained set of responses to systemic insecurity in which institutional protection often fails to intervene before violence escalates. As a result, tools such as pepper spray increasingly appear in public debate as immediate, accessible responses to persistent risk.

The recent authorization of pepper spray sales to women in Rio de Janeiro must therefore be understood not only as a policy decision, but as a response to this environment of insecurity. While such tools can offer a brief window of opportunity to escape an attack, their effectiveness depends on correct use, situational awareness, and a clear understanding of their limitations. Pepper spray is designed to temporarily incapacitate an aggressor—causing intense eye irritation, disorientation, and breathing difficulty—only long enough to allow escape. It is not a deterrent, a warning device, or a substitute for protection.

Improper use can increase danger rather than reduce it. A recent case in São Paulo illustrates this risk: during a robbery, a young woman attempted to react while facing an armed attacker and was shot in the head in front of her father and boyfriend. Similar outcomes have been documented in other armed confrontations, reinforcing that defensive tools are context-dependent rather than universally protective.

Other personal defense methods, including alarms, tactical flashlights, or basic self-defense techniques, should similarly prioritize escape, distance, and attention-drawing over confrontation. Without proper guidance and training, these tools can create a false sense of security. Ultimately, while personal defense measures may reduce vulnerability in specific moments, they cannot replace prevention, protection, and collective responsibility for women’s safety.

Recommendation: The most important step for any individual is to prioritize and follow security awareness training provided by specialists who focus on behavior and how to react in case of aggression. Technical tools are secondary to the mental preparation and behavioral strategies required to de-escalate high-risk situations and ensure survival.

Brazil vs. the World

When placed in a global context, Brazil’s struggle with feminicide and gender-based violence is both part of a wider international crisis and a particularly acute national problem. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and UN Women, around 50,000 women and girls worldwide were killed by intimate partners or family members in 2024, averaging about one woman murdered every 10 minutes solely because of her gender or relationship to the killer. In these cases, the offender is almost always personally linked to the victim, making the violence a betrayal of trust and significantly complicating the victim’s ability to respond or escape. These deaths represent a persistent global emergency that affects every region, with Africa and the Americas showing especially high rates.

In comparison, Brazil’s numbers are significantly troubling even within this global emergency. In 2024, 1,492 women were victims of feminicide in Brazil, the highest total recorded since the crime was legally defined in 2015. This places Brazil among the countries with some of the highest numbers of gender-based killings in the world. According to WHO data and international analyses, Brazil ranks around fifth globally in overall feminicide rates, trailing behind other nations with severe violence levels like El Salvador, Guatemala, and Colombia.

While global estimates suggest that roughly 1 in 3 women worldwide will experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime, Brazil’s survey data reveals that 37.5% of women aged 16 and over reported violence in the past year, one of the highest prevalence rates recorded. This illustrates that Brazilian women face not only high rates of lethal violence, but also widespread non-fatal abuses compared to global averages.

Thus, although feminicide is a worldwide tragedy—claiming tens of thousands of lives annually—the combination of high absolute numbers, high prevalence of gender-based violence, and Brazil’s ranking among the countries with the most feminicide underlines the severity of the crisis in Brazil relative to many other parts of the world.

A Crisis That Demands Collective Action

The persistence and recurrence of violence against women in Brazil points to a broader social challenge that extends beyond individual cases or isolated incidents. The patterns observed over time suggest that gender-based violence continues to be tolerated, ignored, or addressed only after irreversible harm has occurred. This reality reinforces the need to look at feminicide not as an exception, but as the most extreme expression of a continuum of violence that permeates daily life.

Meaningful changes depend on the strengthening of public policies capable of acting before violence escalates, ensuring access to protection, support networks, and education that promotes equality and accountability. At the same time, responses cannot rely solely on the State. Civil society plays a key role in prevention and assistance, companies influence norms through workplace practices and risk management, and the media shapes public perception and awareness.

In this context, Interlira contributes by translating security intelligence into practical awareness. Through safety induction, the company offers structured guidance and training tailored to specific environments, helping individuals, teams, and organizations understand local risk patterns, recognize warning signs, and adopt safer routines. Strengthening awareness and preparedness does not eliminate violence on its own, but it reduces vulnerability and reinforces a broader understanding: violence against women is a collective challenge, rooted in social structures, and addressed through shared responsibility rather than silence, fragmentation, or isolation.

[1] Stalking is unwanted and/or repeated surveillance or contact by an individual or group toward another person. Stalking behaviors are interrelated to harassment and intimidation and may include following the victim in person and/or monitoring them virtually.