Summary

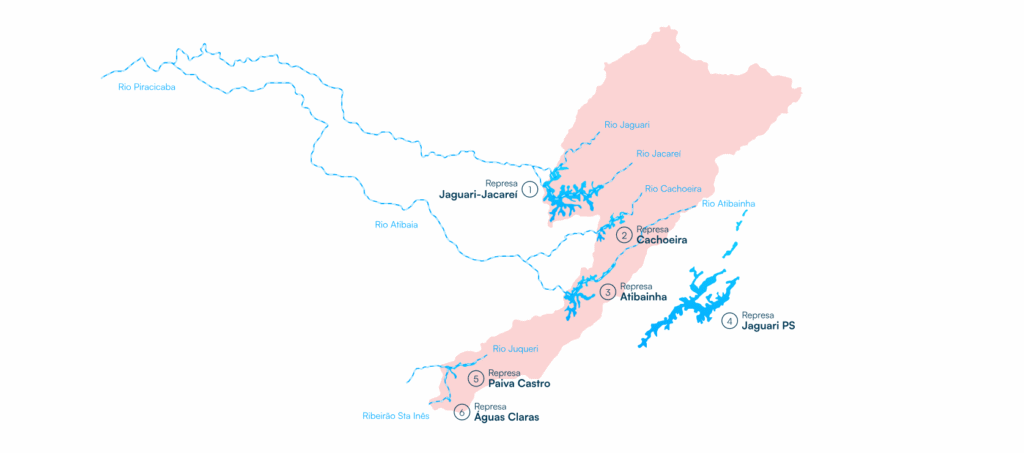

Brazil is currently facing a renewed phase of hydric stress driven by extreme heat, reduced rainfall, and increasing pressure on water reservoirs. This scenario is unfolding alongside a sharp rise in electricity demand, intensifying strain on an energy system that remains heavily dependent on hydropower. As reservoir levels decline and demand peaks, the reliability of energy supply becomes more fragile, increasing exposure to localized outages and operational disruptions. In São Paulo, reduced rainfall has already affected river systems feeding the Cantareira System, increasing pressure on both water availability and energy reliability in the country’s main economic hub.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

Water scarcity is not just an environmental concern; it is a primary driver of energy instability. This volatility directly impacts production, operational costs, and the reliability of power-dependent infrastructure and security systems. As a result, businesses can no longer take grid stability for granted when planning for long-term resilience.

For companies operating in Brazil, the hydric crisis must be understood as a systemic risk rather than a temporary environmental event. Its impacts extend across physical security, operational resilience, supply chains, and financial planning. The convergence of climate variability, infrastructure constraints, and rising demand requires organizations to reassess how water and energy risks are incorporated into strategic decision-making.

Addressing this challenge demands an integrated approach for companies that links climate monitoring, energy reliability, security planning, and continuity frameworks. For decision-makers, this context reinforces the need to treat hydric and energy risk as core variables in security, continuity, and strategic investment decisions. On a macro level, this reality necessitates a transition toward a more resilient and diversified national energy matrix.

Physical security risks

The current water and energy stress in Brazil introduces concrete physical security risks for companies, particularly in regions where the electricity system is operating under sustained pressure. According to operational bulletins from the National Electric System Operator (ONS), the Southern Subsystem entered January 2026 with reservoir levels at a critical 29.5%, the lowest among all regions. At the same time, national energy load increased by 5.6% compared to the same period in the previous year, driven directly by extreme heat.

This imbalance between supply conditions and demand increases the probability of localized outages rather than widespread blackouts. Sector analysis indicates that, while generation capacity exists, the distribution network represents the most fragile layer of the system, especially in the South and Southeast. These localized interruptions pose direct risks to physical security infrastructure, which is highly dependent on continuous power.

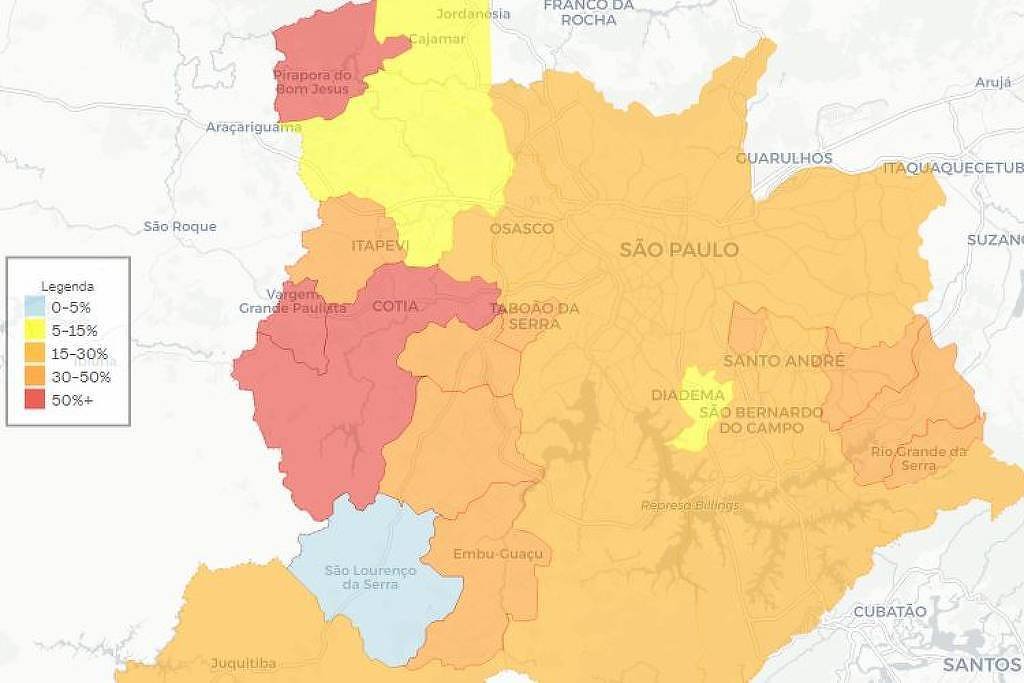

São Paulo represents one of the most exposed environments in the country due to the concentration of critical infrastructure, logistics hubs, industrial facilities, and corporate headquarters. This exposure is reinforced by hydrological stress in the metropolitan region. According to the National Center for Monitoring and Alerting of Natural Disasters (Cemaden), reduced and irregular rainfall during the first months of the rainy season pushed the reservoirs supplying São Paulo to their lowest December levels since the last water crisis. On December 30, the Integrated Metropolitan System registered a useful volume of 26.1%, significantly below pre-crisis levels and even lower than those observed in 2013.

Recent large-scale outages affecting millions of customers demonstrated how grid instability can simultaneously disrupt CCTV coverage, access control systems, and emergency response capabilities across dense urban and industrial areas. In this context, even short-duration outages materially increase exposure to theft, intrusion, and operational disruption.

Impacts on public security

Water scarcity and energy system stress increasingly manifest through social instability, particularly in large urban centers where prolonged service interruptions directly affect daily life. In São Paulo, large-scale blackouts triggered by extreme weather events in December 2025, especially between December 9 and December 13, exposed how energy disruption can rapidly escalate into broader social risk. During this period, millions of residents were left without electricity for extended durations, in some cases exceeding 30 consecutive hours, with cascading effects on communication networks, water supply, and public safety. As electricity and water services failed simultaneously, public dissatisfaction intensified and protests were recorded in multiple areas of the metropolitan region, including the South Zone, North Zone, and municipalities in the ABC Paulista region.

These conditions created an environment conducive to opportunistic crime. During the blackout period in mid-December, reports of robberies and thefts increased in areas left without lighting or surveillance, reinforcing the connection between energy instability, public insecurity, and social disorder. For companies operating in or near affected areas, these dynamics translate into heightened exposure to access restrictions, workforce mobility issues, and increased risk to personnel and assets.

Economic and business impacts

From a business perspective, the economic impact emerged primarily through this social dimension. Protests, blocked roads, and localized unrest disrupted logistics routes, delayed deliveries, and restricted access to facilities. Employees faced difficulties commuting safely, while retail and service operations were forced to suspend activities due to security concerns rather than purely technical outages.

The risk is compounded in logistics hubs, industrial parks, and remote facilities, where security teams may already operate with limited redundancy. Cemaden assessments indicate that even under average rainfall conditions, inflows in systems such as Cantareira are expected to remain below historical norms, suggesting that energy and water stress may persist beyond short-term weather events.

In addition, historical patterns during periods of high Marginal Operating Cost (CMO) further reinforce this risk. Industry reports indicate that rising energy prices tend to coincide with increased theft of physical infrastructure, including copper cables, transformers, and fuel used in backup generators. As electricity becomes more expensive and outages more frequent, physical assets linked to energy systems gain value as theft targets.

In this context, water scarcity and energy stress should be understood as catalysts for social disruption with direct business implications.

Conclusion

The risks associated with the current and projected hydric crisis require a clear shift from reactive responses to a preventive and integrated approach. Energy instability should no longer be treated as an exceptional disruption, but as a structural variable capable of triggering cascading effects on physical security, operational continuity, and economic performance. Under this scenario, fragmented responses are insufficient. Organizations must adopt integrated risk frameworks that connect climate conditions, water availability, energy reliability, and security planning.

Addressing this challenge demands an integrated approach that links climate monitoring, energy reliability, and security planning. For decision-makers, this context reinforces the need to treat hydric and energy risk as core variables in strategic investment decisions.

Driven by the Ministry of Mines and Energy to solidify national security, Brazil is pursuing nuclear expansion as a high-reliability, 24/7 baseload solution. While this strategy leverages a proven engineering record for safety and waste containment, it remains a subject of intense debate as leaders balance these productivity gains against the significant financial burden of Angra 3 and complex public perceptions regarding waste. The National Energy Plan 2050 institutionalizes this ambition by targeting 8–10 GW of new capacity, beginning with large reactors before transitioning to Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) and fourth-generation technologies.