This year’s presidential campaign reached a new phase this August, the 12 candidates were approved by the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) (see Focus). The elections new stage came one month after a case of murder connected to a political provocation hit the headlines. The event sparked debates about political violence and associated to other incidents on the streets and online, solidified fears of an escalation in hostilities.

THE MURDER OF MARCELO ARRUDA

The event is likely another case connected to the widespread anti-PT sentiment in the country. According to specialists, this phenomenon started to gain strength in 2005, after the corruption scandal called “Mensalão”. In 2012 and 2014, it grew with the case’s trial and the Car Wash Operation, respectively. The sentiment polarized politics in the country, led some groups to radicalization and became an important political platform used by politicians in the 2018 elections.

Critics and opponents of the current Government state that President Bolsonaro is part of this group that capitalized on the polarization and that he stimulates violence against his adversaries. An episode frequently mentioned by his opposition is a political rally in Acre, in which he said that people should “shoot PT supporters”. Accused to foment violence, Bolsonaro defended himself stating that during the rally, he used a rhetorical figure. He has also repeatedly published a text declaring that he doesn’t need support from those who are violent. Furthermore, the President has affirmed that violence comes, in fact, from the left-wing groups, and mentioned the knife attack against him in the 2018 campaign as an example.

POLITICAL VIOLENCE ON THE RISE

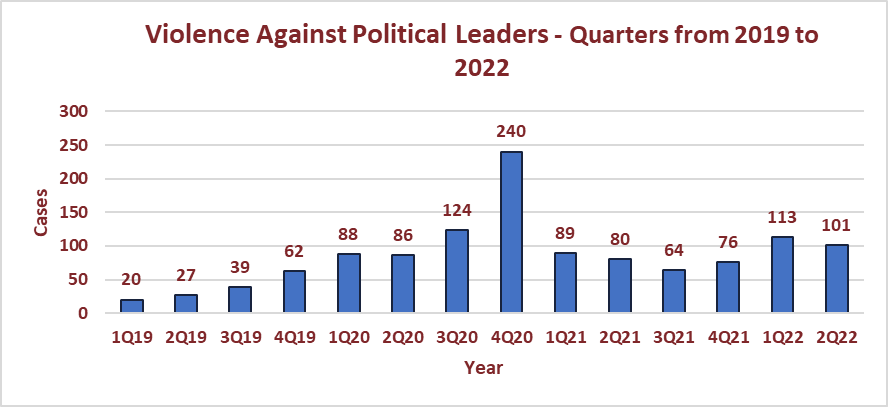

A survey completed by the Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UniRio) showed that political violence is increasing in Brazil. According to researchers, for the last three years, attacks against political leaders in the country have grown 335%. During the first semester of 2022, 214 cases of political violence were reported, while the same period of 2019 had 47.

This year’s numbers represent a 23% increase in comparison to that of 2020, when the last elections took place. Threats, aggressions, and assassinations are among the most common acts against members and former members of the Executive and Legislative, pre-candidates, ex-candidates, candidates, and certain public servants, all of them considered political leaders. Only in the last semester, 45 individuals that fit in this group were killed.

TENSION AND VIOLENCE IN THE PRE-CAMPAIGN

Violent episodes, with verbal and physical attacks, connected to this year’s pre-campaign have been multiplying for a long time throughout the country. Among the most notorious attacks is one from 7 July, when a PT political rally in Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro (RJ), was attacked by a man that threw a makeshift bomb against the crowd. No one was hurt and a suspect was arrested. Andre de Brito, the alleged aggressor, told the Police that his act was a protest over the present ideological polarization that could damage the nation’s future.

Episodes of intolerance have been promoted by supporters of the opposition as well. On 29 June, a group of left-wing protesters harassed Novo’s pre-candidates and hindered their attempt to promote a talk in the Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), SP. Below, other highlights:

- On 1 May, in Belo Horizonte (MG) central zone, protesters against and in favor of President Bolsonaro exchanged provocations and offenses

- On 5 May, a group of protesters surrounded Lula’s car and harassed him as he arrived in Campinas (SP). One of the former president’s guards removed a banner against Lula, escalating tensions

- On 11 May, in Juiz de For a (MG), PT and Bolsonaro supporters threatened each other, and the Military Police intervened

- On 16 June, an alleged Bolsonaro supporter used a drone to pour feces and urine on people at a PT rally in Uberlândia (MG)

- On 21 June, pre-candidate to the Congress Caíque Mafra invaded a Lula pre-campaign event in São Paulo and called him corrupt

- Federal Judge Renato Borelli, who ordered the arrest of former minister Milton Ribeiro in June, suffered a series of online threats. On 7 July, while driving to work, he had his car attacked with dirt and feces

- On 16 July, according to witnesses, a left-wing rally in Praça Saens Peña, Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro (RJ) was interrupted by a group led by the right-wing State Deputy Rodrigo Amorim. The group would have made threats and torn flags apart

- On 26 August, a man campaigning for a candidate for the government of Rio, Marcelo Freixo, was reportedly beaten by seven armed men in Campos dos Goytacazes.

THE ONLINE BATTLE FOR THE PUBLIC OPINION

The growing tensions of this campaign can also be seen online. The virtual world has become an essential space for the political debate, it is where many politicians and their supporters wage a battle for the public opinion. Threats, offenses, fake news, and data distortion are some of the forms through which this virtual fight manifests itself.

One of the virtual tactics uses out of context or fake photos and videos to make people believe that a specific event promoted by a political adversary had almost no participants. The same approach has been used to tell that a given rally had many people present, when in fact it did not. Furthermore, online polls without statistical value made by supporters of some candidates have been spread as if they could disprove the results of a survey released by a research institute.

AN OPPORTUNITY FOR MORE HOSTILITIES?

Now that most candidates have been officially announced, political events will increase. Public appearances, rallies, debates, and similar occasions will become more frequent. This tends to agitate supporters from different sides and create opportunities for attacks, increasing risks.

Sensing this situation, after the latest events, the Federal Police (PF), which is directly responsible for protecting presidential candidates, ordered state forces to reinforce the presidential candidate’s security in the election. The institution sent an order to its 27 state branches, stating that the “current scenario highlights the need for additional efforts, given the aggravation of relations between supporters of the main candidates and also the incidents already registered in the pre-electoral campaign phase”. Moreover, the attack against Bolsonaro, in 2018, and even the assassination of former Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, on 8 July, in a much less violent country, with less firearms circulating, set precedents and indicate that the chances of a tragedy do not seem unlikely.

More data provided by the survey from UniRio endorse this thesis. Data from the last campaign, in 2020, indicate that cases of violence against political leaders increased gradually each quarter as the election day approached.

Some believe that rising tensions could even lead to episodes of civil unrest. For the Supreme Court (STF) Minister and Superior Electoral Court (TSE) President, Edson Fachin, this year’s elections may have an episode similar to the invasion of the US Congress on 6 January, 2021, after the defeat of Donald Trump. Fachin thinks that this could be stimulated by the criticisms made by President Bolsonaro and his supporters against the electronic voting machines’ reliability. They have repeatedly affirmed that the machines are prone to frauds.

Among the events that spread fears of a disaster is the Brazilian Independence Day, which is celebrated every 7 September. Last year, this date concentrated a series of nationwide protests pro and against the government. This year, the traditional parade in downtown rio was cancelled due to fears of attacks and a small event will be held in Copacabana. On 19 August, according to a report by the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo, military intelligence had detected the possibility of radical movements in support of the President of the Republic seeking to infiltrate the with the objective of provoking riot and advocating an unconstitutional military intervention. Such an alert, according to the newspaper, would have been decisive for the cancellation of the traditional military parade. Still, some believe that an attack can happen in the political act that will be promoted by the President in Copacabana, close to the small official event celebrating the independence.

Despite the speculations above, Defense Minister Paulo Sérgio Nogueira, does not agree with Fachin. On 6 July, during a hearing in the Congress, he stated that the Armed Forces are not concerned about a violent action by groups that are contrary to the Brazilian electoral process, as occurred in the Capitol.

To avoid more hostilities, important political leaders demand measures to contain the spirits of the main players of this election. On 11 July, Senate President Rodrigo Pacheco requested that President Bolsonaro, and his main opponent, former president Lula, be more concerned about the attitude of their political followers and repudiate violent attitudes.

In addition, on 24 August, Superior Electoral Court (TSE) President Alexandre de Moraes met with commanders of the states’ Military Police forces and informed them that the Electoral Justice will invest around R$ 100 million in the security of this year’s elections. The resources will be distributed the police and the Armed Forces. A few measures were announced:

- It was agreed to install an intelligence nucleus in the presidency of the TSE with the objective of analyzing the information produced by the police in the country

- The Superior Electoral Court (TSE) is due to vote on Tuesday (30/08) a proposal to restrict the carrying of weapons on election day

- The electoral court forbade voters to carry cell phones to the voting booths. They will have to hand over their devices or any other electronic before entering the voting booth on election day. He cited reports that militias in past elections had demanded videos from voters to prove who they voted for. He also mentioned offering an advantage in exchange for voting and even trying to make videos showing false problems at the polls.

- Metal detectors may be used in exceptional situations, evaluated on a case-by-case basis by the electoral judge

As Brazil’s security context keeps deteriorating, there is a strong probability for political violence to remain and to intensify with the election day approaching. The recommendations below are important to reduce risks:

Recommendations

- Avoid the vicinity of common protest or political rallies locations in Brazil’s main urban centers

- Avoid any association with the Brazilian main political parties, including but not only the PT, PSDB, MDB, PL, PSL, and PDT

- As a basic precaution, avoid all crowds and demonstrations. If caught in a demonstration: try to leave the crowd as quick as possible; seek shelter in a nearby building and wait for the demonstrators to disperse; refrain from taking pictures or using your phone

- Do not wear the Brazilian football jersey or a red shirt, especially near protest zones, as they can be seen as a sign of political affiliation

- Anticipate an increased presence of security forces

- Anticipate possible traffic disruptions in the vicinity of all protests or political rallies and plan itineraries accordingly

- Refrain from discussing Brazil’s political situation, particularly on social media

- Keep abreast of local developments as to the political tensions during the campaign

- Monitor the social media accounts of the main presidential candidates and parties