SUMMARY

In the wake of the unprecedented escape from the Mossoró Federal Penitentiary in Brazil, questions arise about the effectiveness of the Federal Penitentiary System in countering organized crime. Affiliated with the Red Command (CV), the escape highlight the pervasive influence of criminal factions, both inside and outside prison walls. The challenges faced by local communities near the search area underscore the broader issues of living and working in proximity to prisons, revealing the complexities of Brazil’s penal system. As the search intensifies, recent revelations of a Red Command support network add another layer to the intricate web of organized crime involvement.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

Prisoners Escaped Mossoró Federal Penitentiary

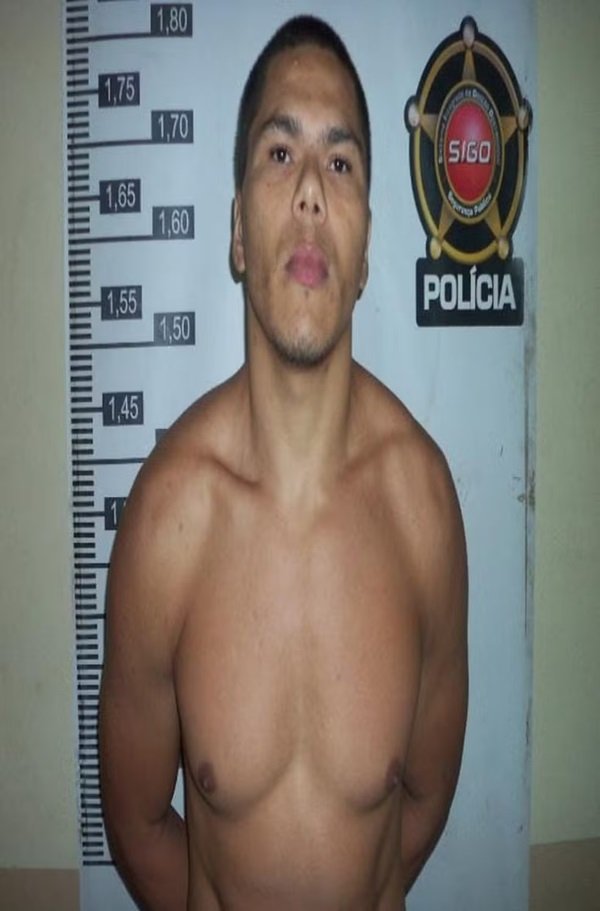

On 14 February, two inmates managed to escape from the Mossoró Federal Penitentiary in the state of Rio Grande do Norte (RN), marking the first recorded escape in the history of the Federal Penitentiary system in Brazil. The fugitives were identified as Rogério da Silva Mendonça, 35, and Deibson Cabral Nascimento, 33, both affiliated with the Red Command (CV).

The escape has raised concerns and questions about the security measures in place, particularly as the federal penitentiary system, including Mossoró, was established to combat organized crime by isolating high-profile criminal leaders and extremely dangerous prisoners. The suspicion surrounding the escape points to the possible use of materials and tools from a construction site within the penitentiary yard.

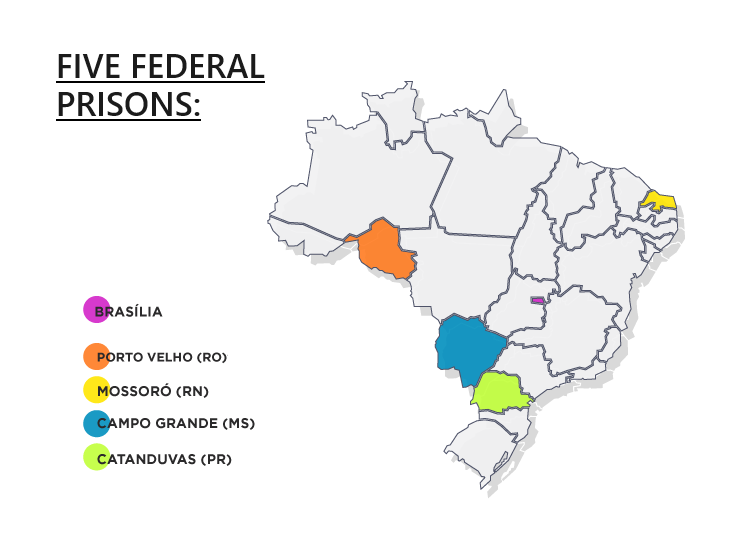

It is noteworthy that the federal penitentiary system has five maximum-security prisons located in Catanduvas (PR), Campo Grande (MS), Porto Velho (RO), Brasília (DF), and Mossoró (RN). While this escape is the first of its kind at the federal level, Brazil has a history of grappling with challenges in state prisons. One of the main cases was the Alcaçuz Massacre, in 2017, which left 27 dead and more than 50 escaped from the same state’s (i.e. Rio Grande do Norte) largest penitentiary.

In another episode, in March 2023, more than 300 attacks orchestrated by a criminal faction were carried out in several cities in Rio Grande do Norte. Criminals shot at properties and vehicles and caused arson in public and private buildings, cars, and buses. According to the Public Ministry, the cause of the attacks was the inmates’ dissatisfaction with the prison conditions, including intimate visits, which had been suspended since the Alcaçuz massacre. This kind of wave of violence is a way that criminals developed to put pressure on public authorities and reply to measures that displease them.

Operation

Following the unprecedented prison break of February, the Justice and Public Security Ministry ordered the immediate removal of the penitentiary management and appointed an intervenor to assume control of the Federal Penitentiary. Additionally, the Federal Police have launched a comprehensive operation aimed at recapturing the two escaped inmates.

At the date of this article, the search efforts are currently focused on the rural areas surrounding Baraúna, adjacent to Ceará. Over 600 security agents, including Federal Police officers, Federal Highway patrol officers, military, and civilian personnel, as well as the National Force, are collaboratively engaged in the recapture operation.

Significant breakthroughs occurred on Thursday (29/02) when farmers reported sighting two individuals in a banana plantation. The task force subsequently confirmed that these individuals were indeed the fugitives. Another pivotal moment took place on Sunday (03/03) during a siege on a farm in Baraúna, where residents reported seeing the two inmates in the early morning. Investigators discovered that the fugitives had broken into an agricultural shed on the property.

The task force’s belief that the fugitives are still concealed in the rural areas has disrupted the daily lives of residents and workers in communities and settlements, primarily comprising farmers. Additional clues during the search include the invasion of two houses and the identification of a farm used as a hideout by the criminals. Ronaildo da Silva Fernandes, the owner of the farm, was subsequently arrested on charges of providing shelter and sustenance to the criminals. Fernandes, however, asserted that he aided the fugitives under duress, citing threats from the duo.

In addition to Fernandes, the Federal Police have arrested five others accused of assisting the criminals in their escape from the penitentiary. All these clues and confirmed activities of the fugitives have been concentrated in the rural areas of the cities of Mossoró and Baraúna.

The challenging terrain, characterized by dense forests, caves, and venomous animals, poses a significant obstacle for the search operation. Despite these challenges, the collaborative efforts of the security agents aim to ensure the swift recapture of the escaped inmates and restore a sense of security to the affected communities.

Indications of Internal Help

Federal Police investigation points out that the circumstances surrounding the escape of the two inmates from the federal penitentiary of Mossoró, in Rio Grande do Norte, suggest the possibility of someone from inside the prison helping with the escape.

At least four pieces of evidence made it possible to create this thesis. The first refers to the metal bars used to remove the lamp from the cell wall. It was from there that the two arrived at the prison’s maintenance site, where there were machines, pipes and all the wiring, known as the shaft.

In the prisoners’ cells and on the roof slab above the cells, metal objects were found, probably used as tools to remove the lamps in the cells. At least one of these metals would be compatible with rebar used in the ongoing renovation, suggesting that the instrument had, in fact, been introduced into the cell.

Through this maintenance duct, the fugitives climbed a ladder and reached the roof of the penitentiary, removed the tiles, and went down the outside of the building until they reached the siding related to a work in progress, which is close to the fence.

A second indication is that it was precisely in this fence that the two prisoners managed to find cutting tools used to break the fence and escape.

Another indication, in the investigation’s view, is the fact that the fugitives managed to make their way to a fence in the dark. A pole that was supposed to illuminate that entire area was turned off by the circuit breaker.

At this point, there is a fourth clue. Even in the pitch black, the fugitives were able to find at least one pair of pliers. The police consider it likely that the tool was left in place precisely to break through the fences. The investigation points out that the images of the fugitives’ action to remove the lamp also suggest that it was a time-consuming and synchronized work, supposedly noticeable through a simple search of the cell. The Federal Police also suspect that daily searches of cells or inmates were not being carried out.

According to the police, so far there are no records or information that indicate support immediately after the escape. However, the Federal Police investigation indicates that the Red Command faction is funding a support network aimed at helping the two inmates.

Red Command Support Network

The criminal faction Red Command (CV) has allegedly been financing a support network to aid the two escaped criminals from the federal penitentiary in Mossoró. This network is believed to be aiding the fugitives in rural areas, offering support for food, drinks, transportation, and potentially firearms.

The police reveal that the fugitives established contact with the Red Command and family members around 09h00 on 16 February, during an incident where they held a family hostage in the rural area of Mossoró and gained access to cell phones.

Following this event, local support for the fugitives was facilitated by an individual residing in Mossoró, suspected to be affiliated with the Red Command due to criminal records. He was the initial person arrested in the case on 21 February, allegedly receiving R$4,500 for his participation.

After dropping off the fugitives near Baraúna, the suspect traveled to Aquiraz, in Ceará, where he reportedly acquired weapons, possibly passed on to the criminals, before returning to Mossoró. Subsequent investigations, including arrests and search warrants, revealed that he did not act alone, getting collaboration from other individuals.

Mechanic Ronaildo Fernandes is another alleged accomplice who reportedly assisted the fugitives and received R$5,000 from the CV for his involvement.

According to new information coming from investigations, the escaped inmates, Deibson and Rogério, have been without assistance for around a week and are encountering difficulties in leaving the search area near Baraúna, contrary to expectations of heading towards the Ceará border. Recent arrests and seizures have disrupted the organized crime’s strategy, resulting in the arrests of at least five individuals suspected of aiding their escape. Deibson and Rogério are reportedly without cell phones, and one of them is injured, as per a witness. Ongoing search operations focus on rural areas between Mossoró and Baraúna, with investigators strongly convinced that the fugitives remain in the region, supported by evidence like home invasions and discovered hiding places in recent days.

Challenges of living near a Prison

The inhabitants of the rural area of Baraúna (RN), a city with approximately 26,000 residents located 37 kilometers from Mossoró, are experiencing days of intense tension. Any movement considered suspicious became a reason to call the police, which, for 18 days, have been in a tireless operation to capture those escaping from the federal penitentiary.

Communication between residents via WhatsApp has intensified, and the exchange of information about any unusual activity results in calls to numbers provided by the police. The reward offered for information leading to the arrest of the fugitives is R$15,000 per inmate.

The operation to search for the detainees drastically changed the peaceful routine of the rural community, where vehicles frequently circulate close to homes. The helicopters used in the operation became an attraction for children, who, upon hearing the noise, took to the streets to watch the flights.

The invasion of a residence in the rural area of the community of Riacho Grande by the two fugitives, where they took a family hostage and stole two cell phones, highlights the palpable challenges faced by those who live close to correctional institutions.

The fugitives’ stay in the house, carrying out activities such as dinner, accessing social networks and even carrying a knife, highlights the boldness and risks associated with the presence of these individuals in the community of Riacho Grande, located just 3 kilometers from the penitentiary. This episode illustrates that, even after escaping, the criminals did not hesitate to invade nearby properties, harming the physical and psychological integrity of residents.

The situation experienced in Baraúna clearly reflects the challenges faced by those who live in areas close to prisons in Brazil. In addition to the constant threat of criminal activities, such as robberies and clashes between rival groups, the possibility of prisoner escapes amplifies the dangers to which communities are exposed. Security, already compromised by social stigmatization and property devaluation, becomes a critical factor in the decision to live and even work near prisons.

Current Prison Population in Brazil

In 2022, Brazil’s prison population reached 832,295 people, according to data from the 17th edition of the Brazilian Public Security Yearbook. Of this total, 621,608 are convicted prisoners, while 210,687 are under provisional detention, awaiting trial. In other words, for every four people incarcerated, one has not yet gone through the judicial process to determine their sentence.

In comparison, this prison contingent is equivalent to the population of more than 5,186 Brazilian cities, according to data from the 2022 Census. Furthermore, it numerically exceeds the inhabitants of three states in the country: Roraima (636,303 people), Amapá (733,508 people) and Acre (830,026 people).

Compared to the previous year, 2021, there was a 1.4% increase in the prison population. It is worth noting that, according to the Yearbook, there is a deficit of more than 236,000 places in the prison system, with the total number of places available being 596,162.

These data reveal not only the continuous increase in the Brazilian prison population, but also the persistent structural gap, reflected in the significant deficit of places in the prison system.

In the worldwide ranking of incarcerated populations, Brazil holds the third position, trailing behind the United States, with approximately 1.7 million prisoners (WBP-2021), and China, where 1.69 million individuals are incarcerated (WBP-2018).

A comprehensive survey conducted by the Grupo de Diários América (GDA) delved into the prison conditions of several nations, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, Peru, Dominican Republic, Uruguay, Venezuela, and the US territory of Puerto Rico. GDA’s findings revealed a host of common issues plaguing the prison systems of these countries. These challenges include overcrowded prisons, deplorable conditions such as insufficient sleeping space and inadequate diet, prolonged periods without receiving sentences, rampant violence (fires, attacks, rebellions, murders, extortion, and threats), corruption, and disorder that allows criminal activities to be orchestrated within prisons, generating millions of dollars for criminal groups.

These pervasive issues within Latin American prisons contribute significantly to the prevalence of organized crime both inside and outside these correctional facilities. The violence against inmates and substandard living conditions are intricately linked to the emergence of major criminal groups. Presently, prisons function as operational bases for faction leaders who are detained there. Moreover, they serve as recruitment grounds for criminals entering for minor offenses, ultimately seeking protection within the umbrella of a major criminal organization.

The domination of these factions within the prison system underscores the critical challenges faced by Latin American nations in curbing the influence and activities of organized crime within their borders.

Brazil’s Prison System Challenges

The growing domination of criminal factions in the Brazilian penitentiary system has become a comprehensive reality, extending across all units of the federation. The First Capital Command (PCC) and the Red Command (CV), originating in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, respectively, stand out as the main influences. These factions, which initially emerged with demands for improvements in prison conditions, such as the CV, in 1979 in the Cândido Mendes prison (RJ) and the PCC in the Casa de Custódia de Taubaté (SP), in 1993, over time, consolidated themselves in the criminal scenario, especially drug trafficking.

According to data from the Ministry of Justice, the CV is present in 21 prisons of the federation, an increase of six compared to the previous year. The PCC is present in 23, two more than in 2022.

A shocking example of the influence of these factions in the prison system and their repercussions beyond the bars occurred in the Amazon region. On 10 June 2023, members of Red Command threatened to kill employees of the Amazonas prison system, refusing to return to their cells, and an amount of R$50,000 was offered as a reward against the murder of one of these employees.

The conflict went beyond the walls and reached the streets of Manaus. Still in June, a prison officer was the target of an attack. On 15 July, a member of the PCC was brutally murdered in the Compensa neighborhood, with decapitation and the criminals displaying his head in front of the house of the mother of the main PCC leader in the state.

This scenario symptomatically illustrates the lack of control by public authorities, which strengthens organized crime. This occurs both due to the system’s inability to isolate leaders who, despite being incarcerated, continue to command crimes, and due to the prison conditions that incentive the affiliation of new members.

Rarity in Europe

Characterized by extreme control measures and heavy restrictions on movement and visits to inmates, the so-called supermax prisons, which inspired Brazilian maximum-security federal prisons are prevalent in the United States and are an exceptionin Europe.

In Western Europe, the United Kingdom’s Closed Supervision Centers (CSC) closely resemble American maximum-security prisons, albeit with a limited scope. Reserved for the most dangerous individuals, approximately 55 people in England and Wales are subjected to this strict disciplinary model. Despite its intended purpose, human rights experts raise concerns about the treatment of detainees and the overall lack of transparency within the system.

The Netherlands introduced an extraordinary security measure known as the extra security regime (EBI) in 1993, responding to a series of embarrassing prison escapes. Located within the Vught prison complex, this model segregates inmates into four blocks with seven individual cells each. Although boasting no reported escapes, incidents of aggression between prisoners have occurred, revealing vulnerabilities even in this high-security setting.

France also has its maximum-security facilities known as Maison central. The Vendin-Le-Vieil prison, operational since 2014, stands out as one of the most heavily guarded institutions in the country. Often housing individuals who experienced violence in other prisons, it employs isolated individual cells where the most dangerous inmates spend 23 hours a day. While maintaining a record of no escapes, the prison has witnessed episodes of aggression among inmates, including fatal incidents. Moreover, inmates have successfully attacked and taken hostages among prison staff and guards, exposing the challenges of maintaining control in such environments.

In conclusion, the European approach to supermax-style prisons reflects the broader global struggle to balance security concerns with human rights considerations. While these facilities aim to contain the most dangerous individuals, incidents of violence and questions regarding transparency persist. The European models, inspired by their American counterparts, underscore the ongoing debate on the effectiveness and ethical implications of extreme security measures within the realm of incarceration.