SUMMARY

Gender-based violence remains a pervasive issue worldwide, deeply connected to social inequalities and power dynamics that disproportionately harm women. According to the UN’s Femicides in 2023 report, 233 women are killed daily by a family member worldwide, with one in three women experiencing such violence in their lifetime. In Brazil, violence against women continues to rise, with incidents of femicide, assault, threats, stalking, psychological abuse, and rape reaching 1,238,208 cases in 2023, as reported by the Brazilian Public Security Forum (FBSP).

These crimes are often rooted in societal and cultural norms, and the rise of technology has created new risks, including data breaches that expose victims’ personal information. Additionally, online and romantic scams exploit women’s emotional vulnerabilities, leading to both psychological and financial harm. Addressing this issue requires challenging cultural attitudes, enhancing legal protections, and improving public awareness to protect women from these evolving threats.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

Femicide in Brazil

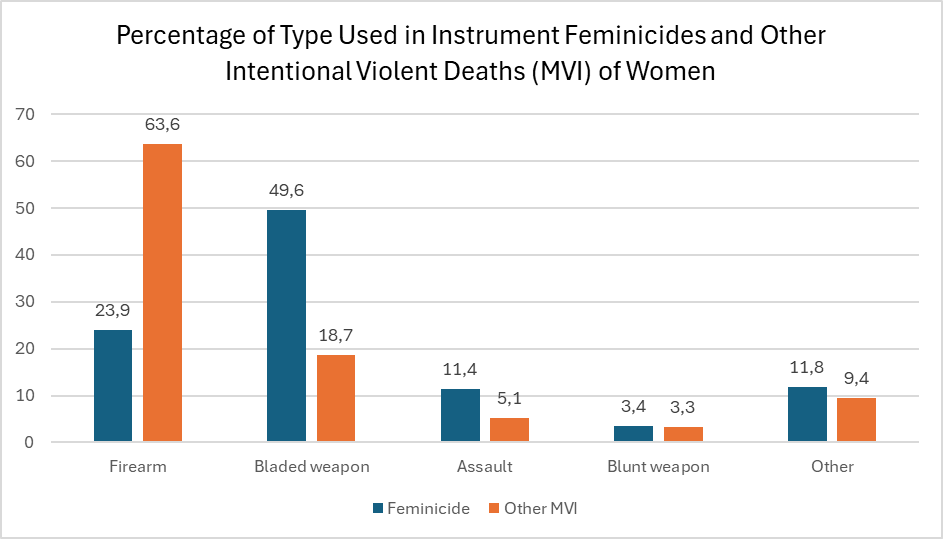

Brazil ranks fifth globally in femicide cases, behind El Salvador, Colombia, Guatemala, and Russia, according to the OHCHR. Brazilian women face significantly higher risks than women in the United Kingdom, Denmark, Japan, or Scotland. In 2023, femicide in Brazil reached a record high since its classification as a crime in 2015, with 1,467 murders—up 0.8% from 2022. Data from the 2024 Brazilian Public Security Yearbook also showed increases in domestic violence-related assaults (9.8%), threats (16.5%), stalking (34.5%), psychological violence (33.8%), and rape (6.5%).

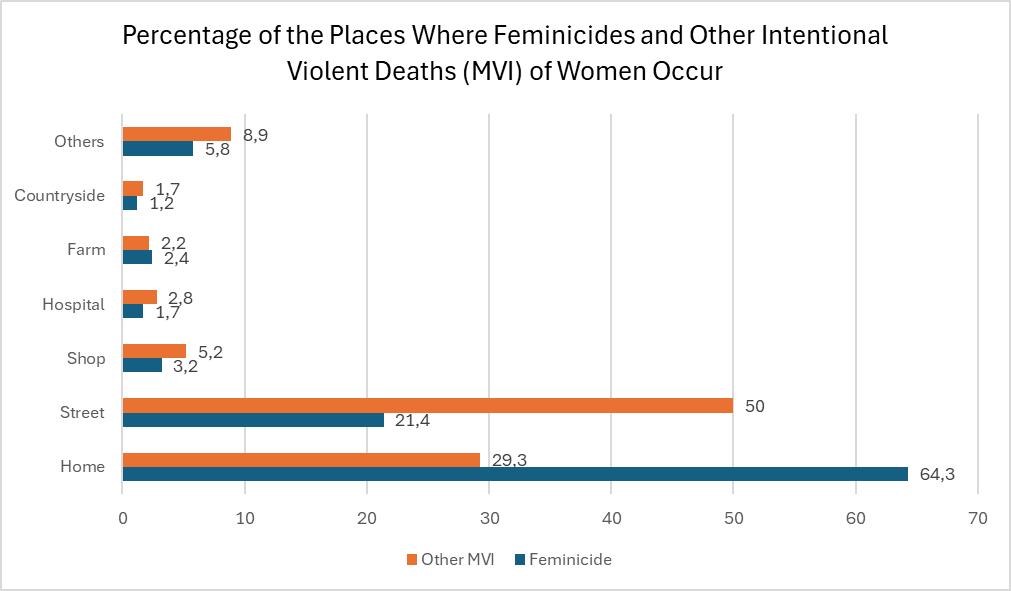

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated violence against women, with 64.3% of femicides occurring at home. This surge is attributed to both increased reporting and higher incidence rates, revealing shortcomings in prevention programs. While the establishment of a Ministry of Women marks progress, underfunding during past administrations and its incomplete operational structure hinder effective action.

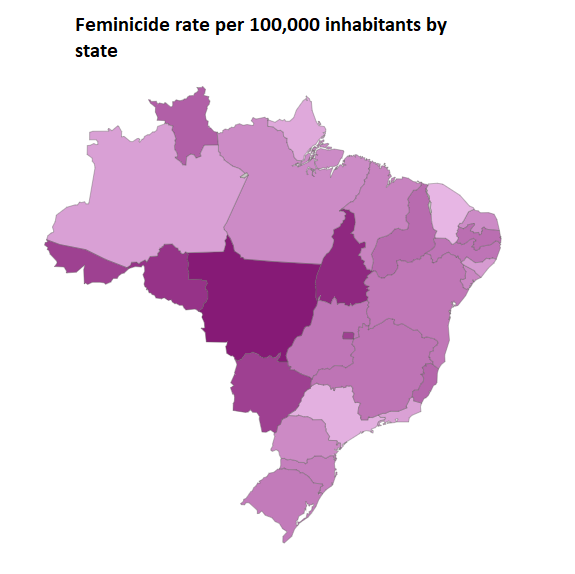

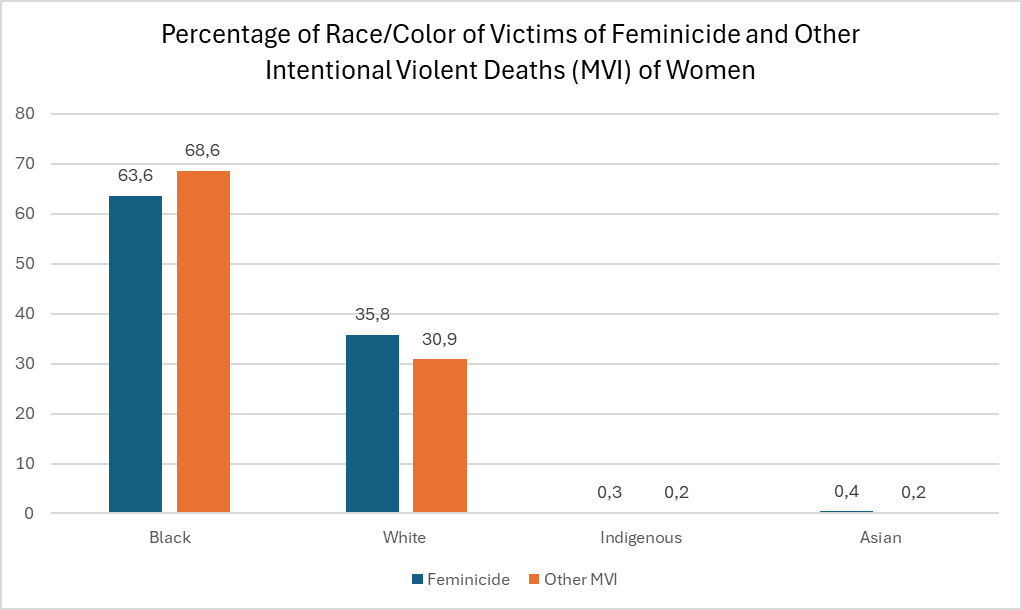

Femicide victims in Brazil are predominantly Black (66.9%) and aged 18–44 (69.1%). Geographical disparities are stark: states like Rondônia (2.6), Mato Grosso (2.5), Acre (2.4), and Tocantins (2.4) recorded rates well above the national average of 1.4 per 100,000 women. In contrast, Ceará (0.9), São Paulo (1.0), Alagoas (1.1), and Amapá (1.1) reported lower rates. However, these variations often reflect differences in crime reporting and data collection, not necessarily safer conditions for women.

Femicide Worldwide

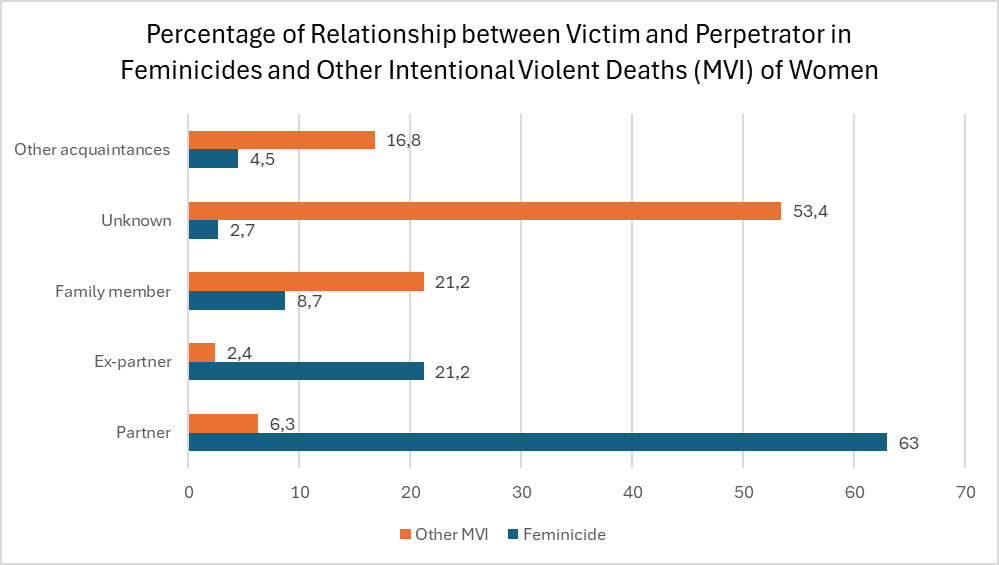

In 2023, over 85,000 women were intentionally killed worldwide, equivalent to almost 233 deaths reported daily, according to UN data. The home remains the most dangerous place for women, with 60% of victims murdered by partners or family members. Femicide transcends borders, social classes, and ages, with the highest prevalence in the Caribbean, Central America, and Africa. In the Americas and Europe, intimate partners are the primary perpetrators, while in other regions, family members are often responsible.

Many victims experienced physical, sexual, or psychological violence before their deaths, suggesting that interventions such as court protection orders could have prevented these tragedies. Although femicide rates have stagnated or slightly declined in some regions since 2010, violence remains deeply embedded in social norms. UN Women and the UNODC emphasize the urgent need to strengthen legislation, improve data collection, and implement effective policies to address this persistent global crisis.

Sexual Violence and Stalking

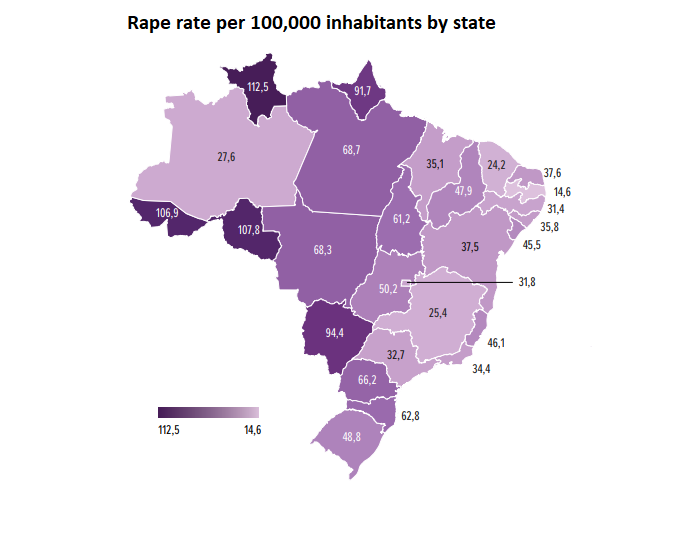

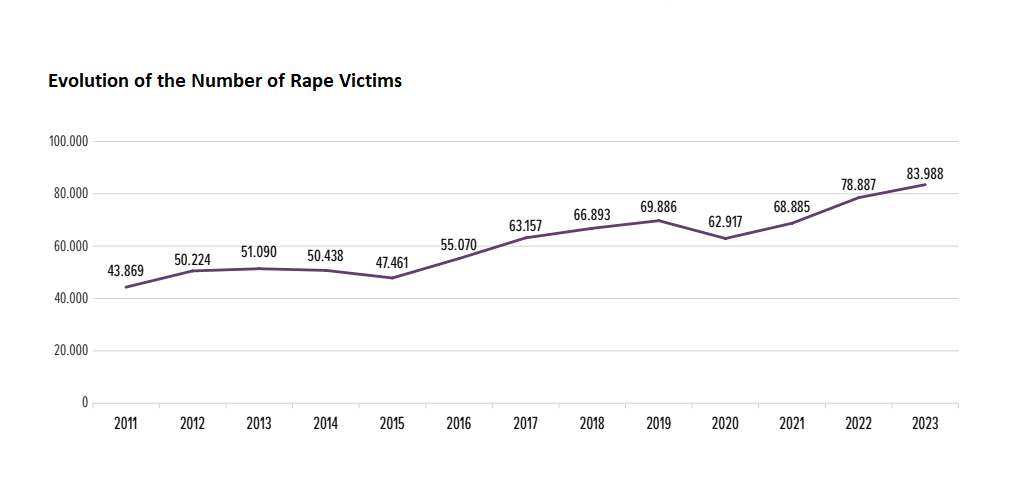

In 2023, Brazil saw a concerning rise in sexual violence and stalking, with one rape reported every six minutes, totaling 83,988 victims per year representing a 6.5% increase from the previous year and a rate of 41.4 per 100,000 women. Other crimes against women also grew significantly, including sexual harassment (28.5%), sexual assault (48.7%), and the non-consensual sharing of intimate content (47.8%).

Stalking emerged as the fastest-growing crime, with 77,083 cases reported—an increase of 34.5% from 2022. This translates to one case every seven minutes and a national rate of 73.7 per 100,000 inhabitants per year. States like Amapá (271.9), Roraima (165.7), and the Federal District (154.8) reported the highest stalking rates, reflecting the severity and widespread nature of this crime in the country.

The Brazilian Public Security Forum (FBSP) attributes the rise in stalking and related crimes to the adaptation of violence to virtual modalities. A stark example of this violence occurred in Frutal, Minas Gerais, where a woman faced seven years of harassment and threats from her ex-boyfriend, despite a protective order. The situation escalated on 1 August 2023, when the aggressor threw an explosive device at her pet shop.

Harassment in Public Spaces

Public transportation in São Paulo remains the place where women feel most at risk of harassment, cited by 37% of respondents in 2024, according to the “Living in São Paulo: Women” survey conducted by the NGO Rede Nossa São Paulo and the survey company Ipec. Streets (24%) and bars or nightclubs (10%) follow, while family environments (3%) and workplaces (2%) rank lowest.

The fear of harassment in public transportation has remained stable compared to 2023, when 39% of respondents also identified it as the most concerning location. Additionally, two out of three women reported having experienced some form of harassment, representing an estimated 3.4 million women in São Paulo aged 16 or older.

Police data further reinforce this concern. In 2023, 601 cases of sexual harassment were reported in São Paulo’s public transportation system, marking a 116% increase compared to 277 cases in 2022. This amounts to an average of one case every 14 hours. Obscene acts also tripled, rising from 14 to 45 cases, while reports of rape reached a historic high of 52, double the annual average of the past decade.

Brazilian law differentiates obscene acts, which are untargeted sexual actions, from sexual harassment, involving non-consensual libidinous acts. Despite a 2018 law and growing awareness, harassment reports continue to rise, highlighting society’s reduced tolerance yet emphasizing the urgent need for stronger policies to protect women in public spaces like public transportation.

Data Protection and the Dissemination of Intimate Images

In recent years, violations of privacy, particularly revenge porn, have become a growing concern, with women being the primary victims. The non-consensual sharing of intimate images, often motivated by personal grudges, leads to severe emotional, psychological, and social consequences. A notable case in Brazil was that of journalist Rose Leonel, whose ex-partner shared intimate photos, including manipulated deepfake content. This case led to the creation of the Rose Leonel Law (13.772/18), which criminalizes the non-consensual recording of sexual content, and Law 13.718/18, which makes it illegal to distribute intimate content without consent.

The scale of the issue is alarming. Between January 2019 and July 2022, Brazil saw over 5,270 legal cases related to the non-consensual sharing of intimate images, with an average of four cases per day. States like Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso, and Rio Grande do Sul report the highest numbers, according to the Council of Justice (CNJ).

Despite these legal reforms, enforcement remains a challenge due to the anonymity of digital platforms and the sophistication of technology. However, Brazil’s General Data Protection Law (LGPD) provides a framework for protecting personal data and holding perpetrators accountable. To address this, preventive measures are vital. Public awareness campaigns can educate people on securing their devices, recognizing phishing attempts, and reporting violations. Digital literacy programs are crucial for empowering women to protect their online presence and understand their rights. Collaboration between tech companies and law enforcement is essential for the swift removal of harmful content.

Vulnerability in Common Crimes

A survey by a consulting firm in 2023 revealed that over 60% of robbery victims in São Paulo are women.

According to the Instituto Patrícia Galvão, that produces and disseminates news, data and multimedia content on the rights of Brazilian women, bus stops and traffic lights are among the places where women feel most vulnerable. Criminals primarily steal cell phones and handbags, which often contain valuable items.

Experts explain that women are preferred targets for criminals due to a broader process of social vulnerability. In Brazilian society, women who are victims of sexual violence are often blamed for their victimization. This societal attitude, combined with the state’s failure to effectively address the issue, has led criminals to increasingly view women as easy targets. The lack of accountability and state intervention creates an environment where such crimes against women continue to escalate. This situation reflects the deep-rooted gender inequalities in the country, reinforcing the need for more effective protection and justice for women.

Perspectives on Violence Against Women

In 2023, violence against women in Brazil continued to rise, as revealed by data on femicides, assaults, and other crimes, compiled by the Brazilian Public Security Forum (FBSP) from police reports, which represent the first official record of a criminal situation.

The scenario remains discouraging. The numbers reflect the current state of the phenomenon, and various theories help interpret the data and understand violence against women in society. A common point in these approaches is the idea that violence has been normalized, becoming a structural part of society. This means that the statistics presented here represent only a fraction of the issue. The violence recorded in police reports, police actions, and judicial protective measures does not reflect the full extent of occurrences. A significant portion of violence does not make it into official statistics, due to reasons such as distrust in institutions, psychological factors like fear and guilt, and the very nature of interpersonal violence, which often happens behind closed doors.