SUMMARY

Piracy and drug trafficking on the Amazon’s rivers are escalating threats, impacting local communities, businesses, and security. Piracy groups hijack cargo and passenger boats, stealing fuel and goods, often using violence. Drug cartels use these waterways to transport cocaine from neighboring countries, adapting to law enforcement restrictions on air routes. The vast geography and lack of policing facilitate criminal activities, strengthening organized crime networks. Criminal activities there increase violence, disrupt local economies and deepen the region’s insecurity.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

The Vital Role of Rivers

Rivers are the lifelines of northern Brazil, playing a fundamental role in transportation, economic development, and energy generation. The Amazon Basin, the largest in the world, extends across the region, with over 22,000 km of navigable waterways that serve as vital arteries for commerce and daily life. In a region where vast distances and dense forests make road infrastructure limited, boats are the primary mode of transport, connecting isolated communities—known as ribeirinhos—to urban centers and essential services. The basin spans several countries—Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela—as well as the territory of French Guiana, and is mostly covered by the Amazon Rainforest.

Beyond transportation, these waterways are crucial for Brazil’s energy matrix. Despite the growth of alternative energy sources, hydroelectric plants still account for 65% of the country’s electricity. The North Region holds 65% of Brazil’s remaining hydroelectric potential and generates over 20.7% of the country’s hydroelectric energy.

The North’s economy is also deeply tied to its rivers. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the region’s economy is primarily driven by plant and mineral extraction, agriculture, and manufacturing, though it remains one of the least industrialized areas of the country. However, its vast water resources—concentrating 68.5% of Brazil’s freshwater while housing only 8.3% of the population—position it as a critical hub for biodiversity and resource management.

Waterways are not only indispensable but also economically advantageous. Transporting goods via rivers offers a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable alternative to road transport. Studies from the Pro-Logistics Movement indicate that waterway freight costs are approximately 53% lower than road freight, translating into annual savings of 1.58 billion reais for grain transportation.

Yet, the same rivers that sustain the economy and energy grid also present vulnerabilities that criminals exploit. Their extensive, difficult-to-monitor networks have become attractive routes for drug trafficking, smuggling, and piracy, threatening both economic stability and public security.

Rivers as Drug Trafficking Routes

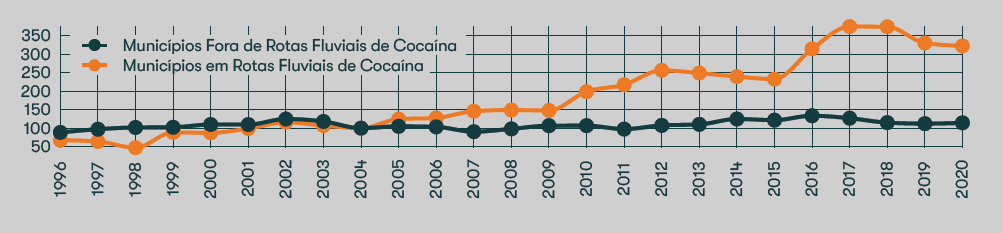

The city of Eirunepé, in Amazonas, has a population of 33,000 inhabitants (IBGE/2022). Between 1996 and 2004, its average homicide rate was 3.7 per 100,000 inhabitants. However, between 2005 and 2020, this figure skyrocketed to 34 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants—an alarming 819% increase. A similar pattern occurred in Cruzeiro do Sul (Acre), where the homicide rate surged from 4.3 to 30.1 in the same period, marking a 595% increase. Both cities are located along the Juruá River, one of the tributaries of the Amazon River, and have become key points in drug trafficking routes.

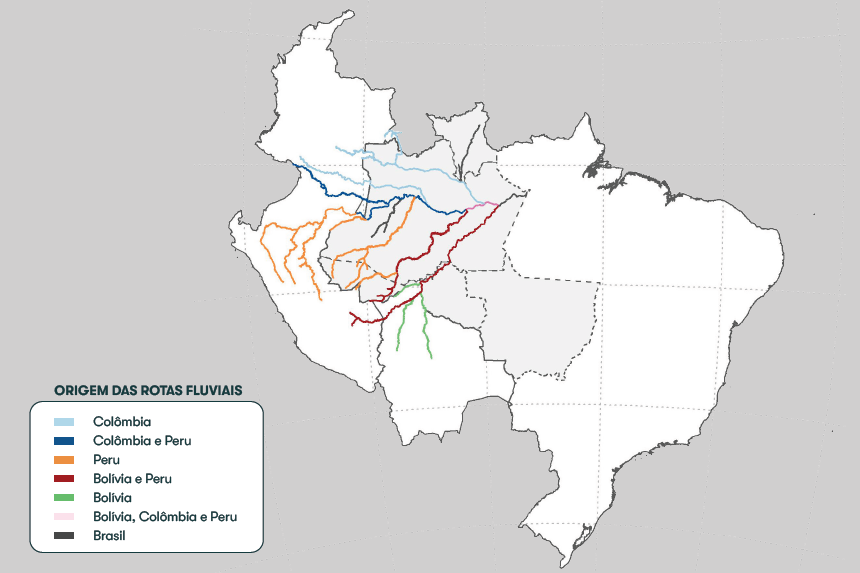

Like these two cities, fourteen other rivers in the region have been identified by Brazilian researchers as “cocaine rivers” due to their role in drug trafficking between Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and Bolivia. These rivers include Abunã, Acre, Amazonas, Caquetá, Envira, Içá, Japurá, Javari, Juruá, Madeira, Mamoré, Negro, Purus, Tarauacá, Uaupés, and Xiê. The increase in violence in these remote areas is closely linked to a shift in drug transportation methods: as air routes became more restricted, traffickers turned to rivers to move illicit goods.

This transition was triggered by a 2004 Brazilian government policy allowing the Air Force (FAB) to shoot down aircraft suspected of smuggling drugs from neighboring countries. With aerial routes under tighter control, criminal organizations adapted by relying on riverine transport, taking advantage of the vast, complex waterways that connect production areas in the Andes to major Brazilian cities like Manaus.

Waterborne drug transport presents unique logistical challenges, requiring traffickers to involve local populations in various roles, such as boat operators, security personnel, storage providers, and equipment suppliers. This deeper integration into communities has exacerbated criminal influence, increasing violence and instability in small cities along the river routes.

The Amazon’s geography has further facilitated drug trafficking. Five of the largest tributaries of the Amazon River originate in the Andes, remain navigable for most of the year, and serve as direct channels connecting cocaine production zones to distribution hubs like Manaus. From there, drugs can be transported to other Brazilian states to be exported via international ports and airports.

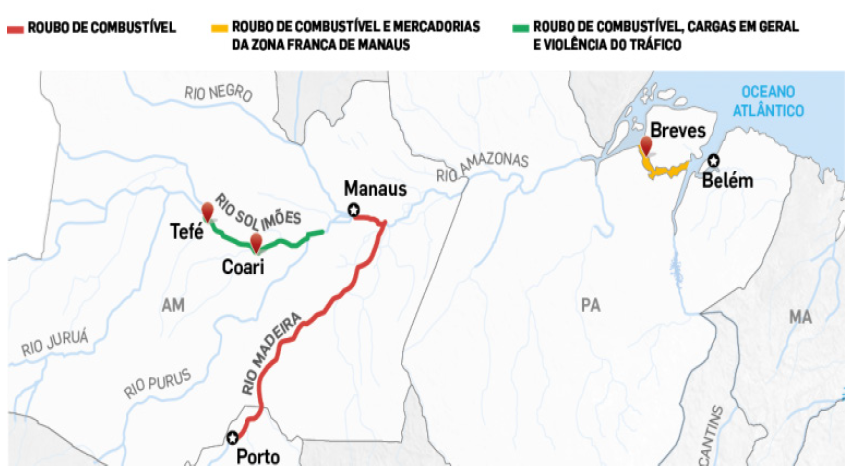

The growing importance of river routes has attracted powerful Brazilian criminal organizations, primarily the First Capital Command (PCC) and Red Command (CV). Originally from São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, respectively, these groups have expanded their operations into the Amazon, battling for control of key trafficking corridors. The PCC has established strong ties with Bolivian suppliers and operates sophisticated logistics networks in the western Amazon, enabling large-scale drug shipments. Meanwhile, the CV has strengthened its presence along the Solimões and Madeira rivers, frequently clashing with the PCC in violent territorial disputes.

River Piracy in the Amazon

In July 2024, pirates attacked two oil vessels on the Solimões River near Jutaí (Amazonas). After exchanging gunfire with security guards on the first vessel, pirates boarded a second boat, assaulting a guard and stealing engines, boats, and personal items.

The National Union of Shipping Companies (Sindarma) points out that, between October 2020 and December 2023, piracy caused losses of R$47 million due to stolen fuel, impacting energy generation and affecting around 17 million people across 460 cities from Acre to Pará.

Unlike traditional maritime piracy, which occurs in international waters, river piracy in the Amazon consists of violent actions targeting goods aboard vessels, attacks on riverside communities, and hijackings of cargo shipments. The term “river piracy” is commonly used in Brazil to refer to these crimes, although the Brazilian Penal Code does not explicitly define piracy, classifying such acts as robbery or theft.

River pirates operate in small, fast boats. They use firearms, machetes, and even homemade explosives to intimidate victims and seize valuable goods. Their main targets include commercial shipments such as food, electronics, and fuel, as well as gold and timber from illegal mining and logging operations. Personal belongings from travelers and local traders are also frequently looted. Many pirates are well-organized and work with informants inside ports and river hubs, allowing them to identify high-value shipments and vulnerable boats. Attacks frequently occur at night and in isolated river sections, where authorities have little or no capacity to respond quickly.

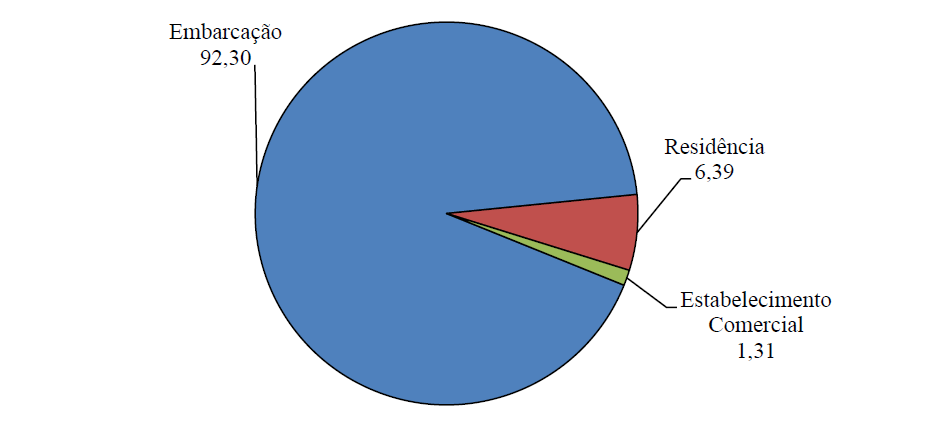

A study by researchers Arthur do Rosário Braga, Emmanuelle Pantoja Silva, Clay Anderson Nunes Chagas, and Silvia dos Santos de Almeida analyzing 689 police reports from Pará (January 2017 – October 2021) found that over 92% of crimes occurred on boats, with the remainder targeting homes and riverside businesses.

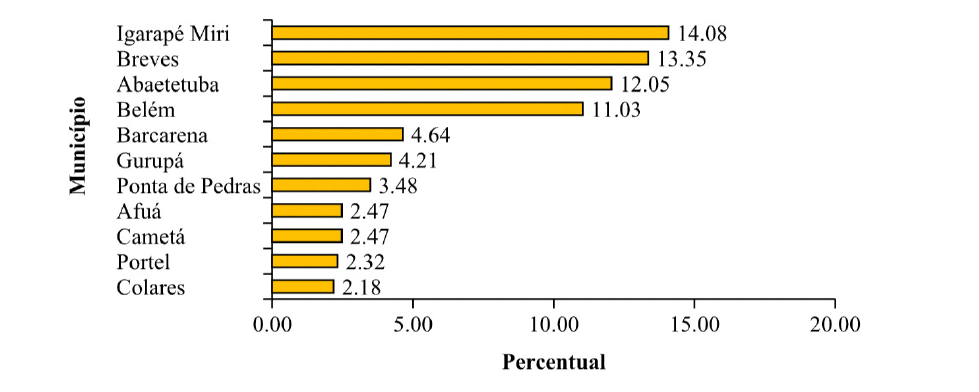

Criminal activity is highly concentrated in certain areas. Of the 59 cities in Pará reporting incidents, over 70% of crimes occurred in just ten cities, with Igarapé-Miri, Breves, Abaetetuba, and Belém notably affected. Incidents peak during certain months, especially in May and February, and commonly occur on Thursdays and Fridays.

Criminal Gangs

The rise of organized crime on the Amazon has led to the increasing involvement of major criminal factions in river piracy. Groups like the Red Command (CV) and the First Capital Command (PCC) have expanded their activities beyond drug trafficking and now control piracy operations along key rivers. These factions use piracy as a secondary source of revenue, funding their broader criminal enterprises. Local independent gangs also engage in piracy. In some areas, criminal gangs also provide “security” services to illegal gold miners and loggers.

Government Responses, Challenges, and Perspectives

Criminal activities links to the rivers remain a major challenge due to the sheer size of the Amazon, the lack of adequate policing resources, and the criminals’ ability to adapt. One of the main obstacles is the limited law enforcement presence, as many river police units lack patrol boats, funding, and personnel to effectively counter pirate attacks. Corruption and complicity further weaken enforcement, with some local authorities and law enforcement agents suspected of colluding with criminals.

The Amazon’s River routes have become critical corridors for both piracy and drug trafficking, creating significant security challenges for businesses operating in the region. Criminal groups have adapted swiftly to enforcement measures, shifting their methods to evade detection, while the region’s vast geography and limited state presence further complicate effective policing.

Despite these challenges, the Amazon remains a vital economic hub, requiring businesses to strike a balance between opportunity and security. For companies conducting operations on the Amazon, a proactive and multi-layered security approach is essential. Regular risk assessments, close collaboration with law enforcement agencies, and implementation of strong security measures are necessary to mitigate risks.