The Red Command (CV) has consolidated its position a one of Brazil’s most dominant criminal organizations, expanding its territorial control and economic influence across much of the country. In Rio de Janeiro alone, the faction controls nearly two-thirds of all mapped communities and operates in 70 of 92 municipalities, funding its power through the systematic exploitation of local utilities, transport, and extortion schemes. Its decentralized “franchise” model allows regional leaders autonomy while ensuring loyalty to the faction, fueling continuous growth. Armed with sophisticated weaponry and expanding even into states like Pará—where it allegedly threatened infrastructure near the COP30 summit—the CV’s reach now reflects a national security challenge, blurring the lines between organized crime, political corruption, and state fragility.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

Territorial Expansion, Economic Power

The large police operation in the Red Command’s (CV) headquarters, on 28 October, drew attention to the power of this criminal organization. According to experts, the criminals’ force is directly connected to the group’s accelerated territorial expansion and how it has been exploiting people living under its control.

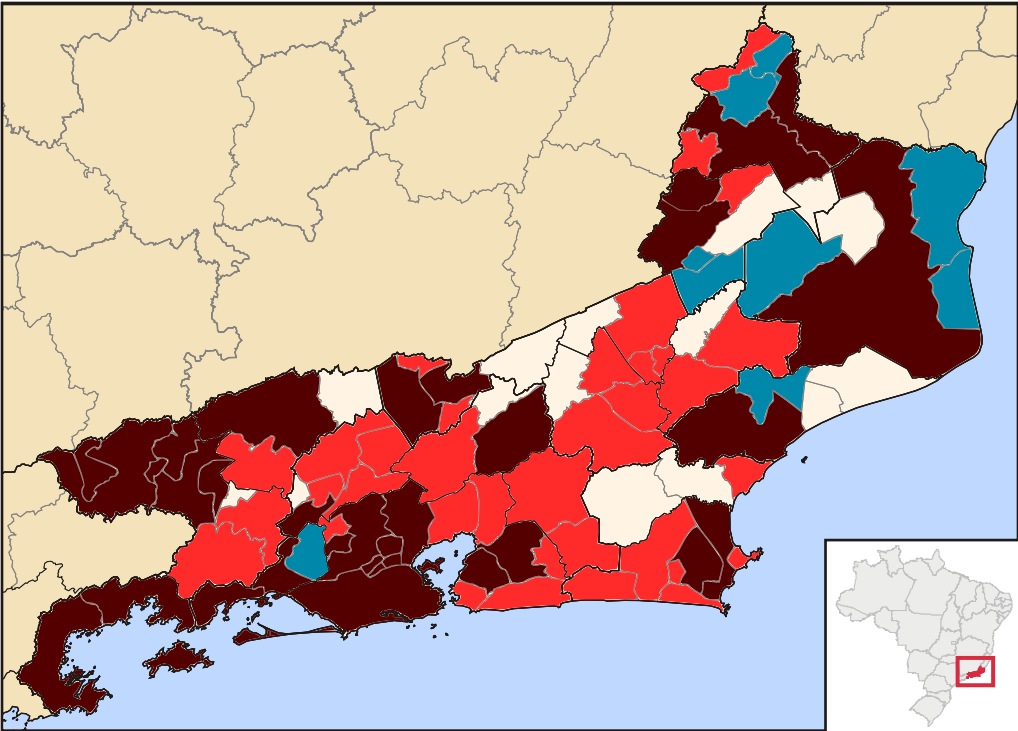

A police report disclosed by the media recently shows the widespread presence of the Red Command in the state of Rio. This criminal group is already in 70 of the 92 municipalities in Rio de Janeiro state (76%). The survey conducted by the Military Police identifies all the communities in the state where criminal groups operate in a structured manner. In 36 cities, CV operates in isolation, without the presence of another faction. And only 15 cities do not have the consolidated control of a criminal group. Of the 1,648 locations mapped, 1,036 (62.8%) are controlled by CV; 340 (20.6%) by TCP; 229 (13.9%) by the militia; and 43 (2.6%) by ADA.

The connection between territorial control and power lies in the economic exploitation of the territories, replicating typical militia activities. The gang’s priority became generating revenue from gas, electricity, water, internet, alternative transportation, and extortion. CV’s focus on the economic exploitation of territories led the faction to invest even more in expanding its areas of operation over the last four years, resulting in increased revenue and income for the group.

However, this also represents a loss of market for legitimate businesses, like internet companies. One of these companies reported that, in only one city in the East Fluminense region, its area of operation fell from 90% to 30%, including locations where the company’s vehicles cannot even circulate. The loss of nearly 20,000 subscribers to providers directly linked to CV was reported.

Franchise Model

The CV does not have as vertical and centralized a structure as the First Capital Command (PCC), but it grew across the territories through model-like franchises. The ways of making money, therefore, vary according to each leader, who continues to have obligations to the faction but has a certain freedom to act as they wish in the territory they control.

Firepower

The Red Command now possesses a modern, expensive, and highly lethal arsenal, with automatic rifles (FAL, HK-G3, AR platforms) with optics and high-capacity mags costing up to R$70,000 each and capable of striking targets from 400 to 500 meters. During the October 28 operation, police seized over 100 rifles and drones equipped with explosives, showing the faction’s increasing military sophistication. Experts note that these weapons, often imported or assembled from illegal parts (“Frankenstein” models), reveal an alarming escalation in firepower. Despite major seizures, analysts warn the faction can quickly replenish its stock, underscoring the limits of current security strategies and the persistence of organized criminal control across Rio’s territories.

Gritzbach and the PCC

One year after the execution of whistleblower Antonio Vinícius Lopes Gritzbach at São Paulo’s Guarulhos Airport, investigations continue with the crime’s masterminds still at large. His testimony had exposed deep corruption between police officers and organized crime, revealing PCC and CV money-laundering schemes through fintechs, real estate, and football. The killing—carried out by PM officers allegedly under orders from both factions—sparked operations that led to 27 police arrests for murder, corruption, and collusion. Despite major crackdowns, fugitives remain protected in CV strongholds, illustrating the enduring convergence between organized crime and sectors of Brazil’s security forces.

Threat in COP30

The Federal Police launched an investigation into an alleged threat by the Red Command against an energy substation in Marituba, Pará, amid the COP30 summit in Belém. A man claiming to be from the faction reportedly ordered workers to halt construction and daily operations, prompting the concessionaire Verene to alert authorities. The PF seeks to determine whether the incident is linked to organized crime or an isolated act. Security remains reinforced as over 1,100 agents and advanced anti-drone and communication systems are deployed to protect the international event and ensure operational safety in the region.

The Red Command’s expansion did not happen only in Rio de Janeiro, but also across the country. The gang is also present in 25 out of the 27 federal units of Brazil, including Pará. The state’s capital, Belém, where COP30 is taking place, is predominantly controlled by the CV.

Analysis:

The Red Command (CV) has become one of Brazil’s most significant security threats, present in 25 federal units. Its power rests on territorial domination and the economic exploitation of local utilities, transport, and extortion, turning communities into revenue sources while displacing legitimate businesses and weakening state authority. This criminal governance model blends economic control with coercion, eroding public confidence in institutions.

CV’s decentralized “franchise” structure gives regional leaders autonomy while ensuring loyalty, making the group flexible and hard to dismantle. Recent seizures of high-powered rifles, drones, and improvised “Frankenstein” weapons reveal increasing militarization and access to global illicit supply chains. Such capacity allows the faction to maintain resilience despite major police operations.

The intersection of organized crime and corruption deepens the national risk. The Gritzbach case exposed collusion between CV, PCC, and police forces, while a recent threat against a Pará energy substation shows the group’s reach into strategic sectors. CV’s presence across Brazil reflects its evolution from a regional gang into a multi-regional criminal network capable of influencing both the economy and internal security.

Sources: A Folha de SP [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]; G1; O Globo.