In this month’s issue, we release the first part of a Security Overview of Brazil base on data disclosed by the 2023 Brazilian Public Security Yearbook and additional sources. We begin describing the scenario of crimes against life, using data about the intentional violent deaths (IVD) by region and by state. Then, we approach the topic of the evolution of the firearms market, which has been in the center of debates about violence. The role of organized crime in the country is also discussed as the main violence driver, followed by the description of areas of special concern due to influence of criminal groups, which continue to expand. In the urban areas, the critical issue of drug consumption and the proliferation of crimes associated is explained, in addition to the negative perspective brought up by new synthetic drugs. Lastly, the general condition of the Brazilian prison system is described, as form of alert to the risks it concentrates.

Next month, we will debate the modifications in the dynamics of property crimes, with the fall of robbery cases and the ascension of frauds and variations of kidnappings; the persistent political violence; hate crimes; violence against women and in schools.

Summary

Every year, the Brazilian Public Security Forum (FBSP) publishes the Brazilian Public Security Yearbook, which is the broadest portrait of Brazilian public security. Relevant data of crimes perpetrated in all the states are collected, organized and analyzed, producing a unique unified description of the current situation and the ongoing trends in the sector. Based on this document, recently released, and on other additional data, an overview of the country’s security conditions is presented through some of the most relevant topics: crimes against life; firearms and violence; areas of special concern; drug trafficking; and the prison system.

Crimes Against Life

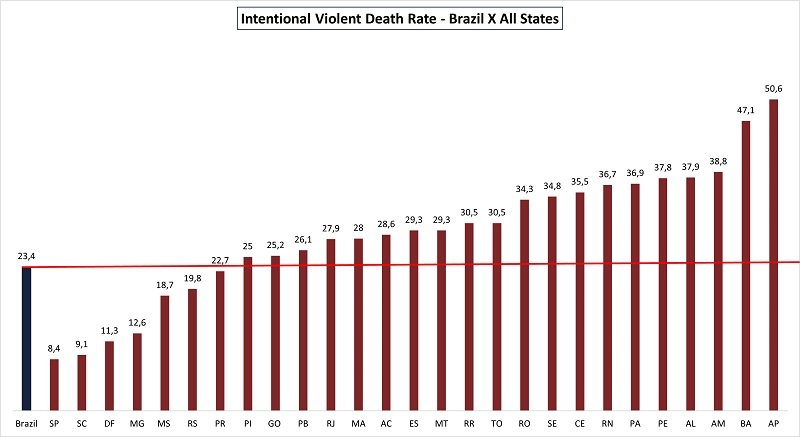

In 2022, Brazil recorded another decrease in the number of intentional violent deaths (IVD). The total reported according to the FBSP, 47,508, represents a 1.9% decrease in comparison to 2021. The result is the smallest recorded in 12 years and the second ever recorded by the institution since it started in 2006. It is only above the numbers from 2011, when the historical record started to be released. In relative terms, calculations indicate 23.4 IVDs per 100,000 inhabitants. The rate is a 2.4% drop from that of 2021.

The team behind the report stresses that the finding is good and should not be undervalued. However, despite the improving scenario, they highlight the importance of understanding that the country has not solved its endemic problem of violence.

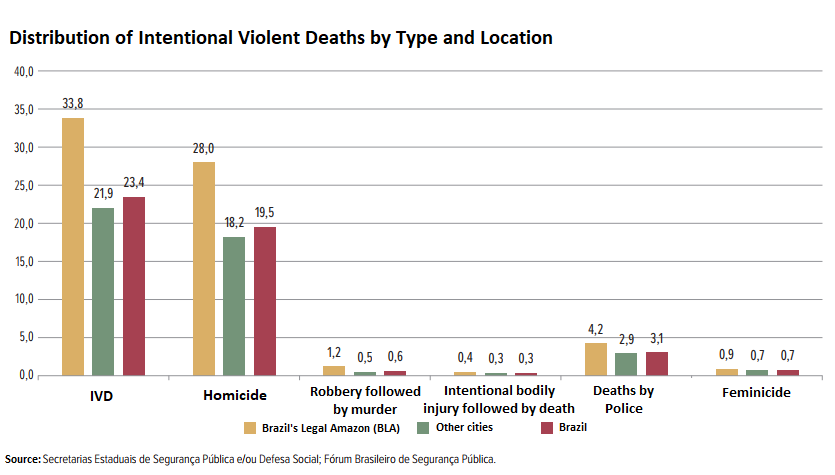

The number of homicides is an adequate kind of data to understand this warning. The IVD used by the FBSP is a more complete way to describe the violence under Brazilian standards. It represents the sum of intentional homicides (regular homicides, feminicides and policemen killed), deaths by police forces, robbery followed by murder, and intentional bodily injury followed by death. However, it is not an international reference, but intentional homicides are. In 2022, this category was 83.4% of the IVDs recorded, or 39,629, which in relative numbers is 19.5 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. The rate is almost twice the United Nations reference value (10 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants), above which violence is considered epidemic. It is also quite above the results from developed countries, like France, which had in 2022 a rate of 1.4.

The analysis of the distribution of violent deaths by region showed that the Northeast had the biggest rate per 100,000 inhabitants, 36.8. The North came in second place, with 36.5 homicides, followed by the Central-West, the South and the Southeast, respectively with 22.6, 18.2 and 14.1.

Researchers say that the regional analysis brings up a picture of a very heterogeneous national context. Even though the number of homicides is falling in Brazil, not all regions follow the movement. In the Southeast, the South and the Central-West regions, the trendlines are pointing down, but in the Northeast it is almost flat, while in the North there is a movement of increase. Such results indicate that the regions have their own dynamics, thus the security scenarios can vary, despite common influences.

This heterogeneity is seen among the states too. São Paulo had the lowest rate, 8.4 IVDs per 100,000 inhabitants; while Rio de Janeiro, from the same region, had a result more than three times of its bigger neighbor, 27.9. Still, numbers can go way beyond that. In Amapá, 50.6 IVDs were recorded, the worst result for a state in 2022. 20 states are above the national average (23.4) and 6 states, and the Federal District are below.

For the FBSP experts, the reduction in the country’s number of violent deaths came for a few reasons:

- The professionalization of the Brazilian drug market. After a bloody war in 2016-17, the factions learned to regulate their relationship, reducing the total number of fatal conflicts

- Professionalization allowed better governmental control over leaders, now, in general, arrested and under monitoring in federal prisons

- Gangs’ consolidation of control over territories, also reducing conflicts

- The creation of new programs and other public policies, like the Pact for Life (Pacto Pela Vida), in Pernambuco

- A reduction in the number of young people in the country, and a reduction in the population growth rate. The age group the most affected by lethal violence are young males, since they are the group with which the gangues have the biggest appeal.

- The creation, in 2018, of the Single Public Security System (SUSP), which coordinated federal and states’ efforts of the sector, and allowed the allocation of resources

Firearms and Violence

During Jair Bolsonaro’s mandate, the gun laws were made more flexible, allowing an increase in the acquisition of firearms across Brazil. From 2018 to 2022, the number of people with a weapon license increased seven times, reaching a total of 783,385. The amount of ammunition sold increased by 147% in comparison to 2017; 420.5 million were sold only in 2022.

The expansion led to debates about public security policies, especially because firearms are the most used tool to kill in Brazil. 76.5% of violent deaths were committed with firearms in 2022. Furthermore, cases of people using their registers to legally acquire weapons that were resold to criminals fueled discussions.

Main Violence Driving Force: Organized Crime

Organized crime is one of the central factors behind the country’s armed violence. They are responsible for most part of the intentional violent deaths, since a large part of them are the result of gangs’ fights, both against the police and among themselves. They are also vector of crimes against property.

A special edition of the 2022 Brazilian Public Security Yearbook showed that there are in Brazil, at least, 53 organized crime factions.

The main source of income for these groups is drug trafficking. They benefit from the fact that the country is both, a great consumer market, and an important exporting route for drugs produced in Andean countries to reach Europe and Africa, particularly cocaine and marijuana.

All over the country, poor neighborhoods are dominated by heavily armed gangs, which pose high risk to people living in the community and around it, in addition to unsuspecting travelers that enter their territory and can be shot.

Drug traffickers are connected to many other criminal activities. The most profitable ones are contraband, kidnapping, express kidnapping, bank/ATM/cash transport/jewelry/car robbery, burglaries, scams, extortion etc.

For instance, in São Paulo, burglaries to high-standard homes and kidnappings of all kinds are perpetrated by specialized groups of Brazil’s largest faction, the First Capital Command (PCC). In Rio de Janeiro, cargo and car robbery are specialties of members of the three major gangs present in the state, including the Red Command (CV), the second most powerful faction in the country.

Area of Special Concern – The Amazon Forest and the Border with Andean Countries

By 2006, factions started an expansion through contacts made in the newly inaugurated federal prison system. The major criminal groups either absorbed the smaller local ones or forced them to merge into bigger ones to survive.

The result of this process is now seen with the solidification of trafficking routes in the Amazon Forest, where criminals also got involved in other illegal activities: logging, mining, hunting, fishing, and land grabbing. This led to deadly conflicts with rival factions, indigenous people, police forces, and preservationists. Meanwhile, violence also increased in the urban centers, where gangs started to fight over the control of drug selling points. As a consequence, the so-called Legal Amazon now has an IVD rate 54% higher than that of the rest of the country, which represent 33.8 IVDs per 100,000 inhabitants.

Moreover, the association of traffickers with illegal miners and loggers is behind a new humanitarian crisis in the North region, which gained headlines in January 2023. In addition to issues raised by Venezuelan migrants, now authorities in the North have to deal with thousands of indigenous people starving to death due to the contamination and destruction of environments used for fishing and hunting. Many have also become severely ill after being contaminated by mercury.

Public authorities have implemented a campaign to repress illegal activities in the area. However, as this occurs in poor states, with few economic opportunities, this creates a dilemma, because illegal logging and mining are some of the only economic alternative for many locals. An efficient repression generates a wave of unemployed workers that can even be attracted by opportunities in the organized crime.

Drug Trafficking and Crimes Associated

The U.N.’s Global Report on Cocaine 2023 showed that the production of this drug grew by 35% from 2020 to 2021, reaching a record. During the pandemic, drug factions found more difficulties exporting the production. Though, this likely helped the local gangs by boosting internal consumption, which is presumed based on the fact that more deaths connected to cocaine consumption were recorded in the same period.

The consumption of illegal substances continues to hamper urban security by leading to the formation of “drug consumption hubs”, commonly known as Cracolândias. These degraded urban spaces, where mostly cheap drugs are sold, scare away clients of stores and local services and are connected to increases in petty crimes. For instance, in São Paulo, the most famous Cracolândia took a nomad stance, moving everyday to a new block in the capital’s central area, rising robberies and thefts in many neighborhoods, and forcing business to close. Theft of valuable structures exposed in public spaces started to be reported more frequently. Manhole covers, copper wires, and all types of metallic structures are targeted, which often hamper public services: street lighting, traffic signs, internet and energy transmission, trains system and more.

In São Paulo, cases of extortion for protection began to be reported after security conditions worsened near the Cracolândia. News revealed that criminals would be demanding payments to remove the drug users from a specific area. This scenario repeats itself in other regions of the country. In Rio de Janeiro city, for example, 14 cracolândias were mapped in 2022, and increases in property crimes were observed in the areas where they were located.

Reports have also shown the appearance of new drugs, often stronger and cheaper, such as the synthetic marijuana (K2, K4, K9). According to São Paulo Public Ministry, five years ago, 95% of the apprehensions involved marijuana and cocaine. Now, synthetics have grown from 5% to 15%. Another novelty is illicit fentanyl, an extremely potent chemical, at least 50 times more potent than morphine, and addictive, which has been found in Espírito Santo state and in São Paulo.

Prisons and Gangs

Brazilian Public Security Yearbook revealed that, in 2022, the prison population in Brazil reached the total of 832,295. The yearly growth rate of the prison population is around 1.4%, The result places this country in the third position among countries with the largest prison population, behind China and the US.

According to the Yearbook, there is a deficit of more than 236,000 places in the prison system. Other issues include precarious detention conditions, thousands of pretrial prisons, corruption, violence and the presence of organized crime.

Map that compares Brazil with other Latin American countries. Experts believe that the facts are alarming, since they create great conditions for the proliferation of criminal organizations, rebellions, crimes orchestrated from within the prison and more.