Summary

Over the past decade, Brazil has witnessed a profound transformation in the way organized crime operates. What once depended primarily on territorial control and drug trafficking has evolved into a sophisticated economic enterprise. In the past few months, police operations coordinated by Brazil’s Federal Revenue (RFB), especially “Carbono Oculto” (Hidden Carbon) and “Spare”, revealed that the First Capital Command (PCC), the largest and most powerful criminal organization in Brazil, has embedded itself in legitimate markets—such as fuel distribution, logistics, and financial services—using these sectors to launder billions of reais generated by criminal activities and expand its influence. Through fintechs, shell companies, and investment funds, illicit capital has merged with Brazil’s formal economy, creating a hybrid system that blurs the boundaries between legality and criminality.

This Content Is Only For Subscribers

To unlock this content, subscribe to INTERLIRA Reports.

Infiltration into Legal Economic Activities

In September and October 2025, a series of police operations across São Paulo and the Baixada Santista region exposed the depth of the PCC’s infiltration into Brazil’s legal economy. On 25 September, the RFB and the police carried out operation “Spare”. This new action executed 25 warrants against individuals and companies involved in the fuel sector, targeting a network suspected of laundering criminal proceeds and evading billions in taxes.

Weeks later, on 4 October, investigators revealed that several of the suspects were partners in 33 gas stations across the Baixada Santista. A subsequent operation on 21 October focused on gas stations in coastal cities such as Santos and Praia Grande, where irregular fuel sales and connections to the PCC were identified.

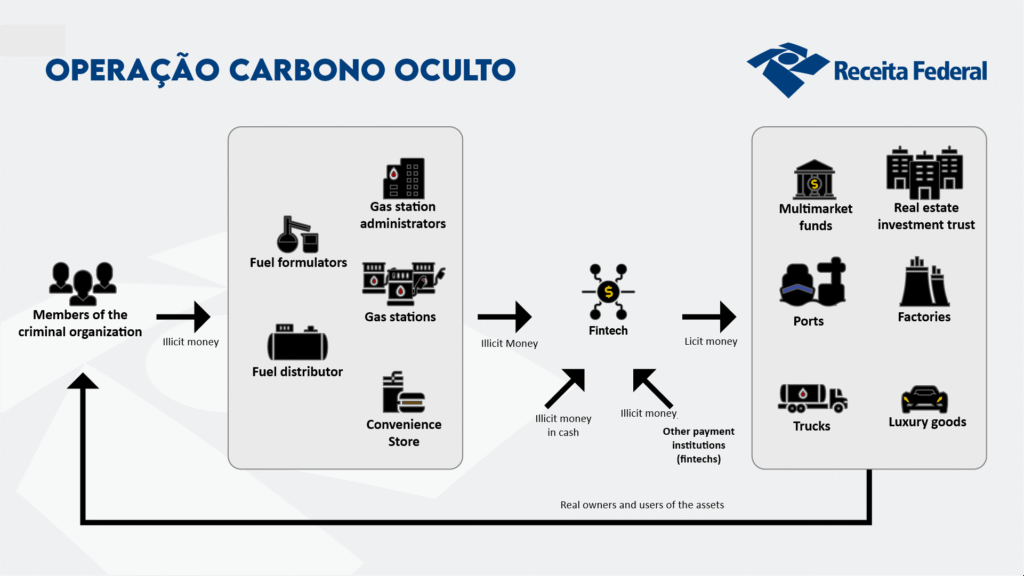

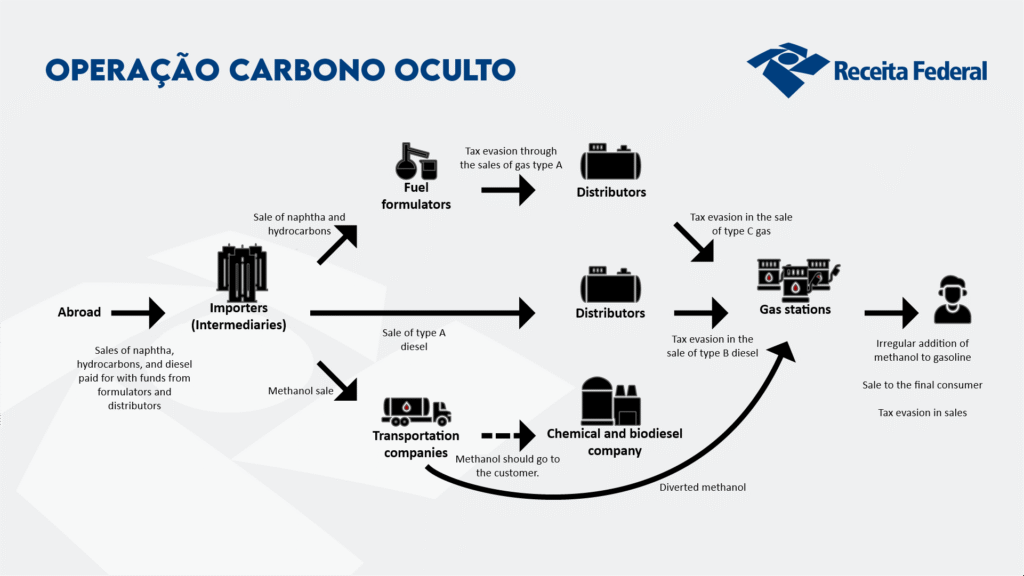

These investigations confirmed that the fuel distribution sector had become a key front for organized crime. Gas stations, transport companies, and ethanol distributors were used to move and disguise illicit profits through a mix of legitimate sales and fraudulent transactions. Authorities found evidence of fuel adulteration, under-reporting of sales, and large-scale tax evasion, all of which helped generate and launder vast sums of money. The operations also revealed networks of shell companies, straw owners, and holding structures designed to hide true ownership and prevent financial tracking.

The attractiveness of this sector lies in its high cash turnover and complex logistics chain, which includes importers, chemical suppliers, distributors, and retailers. Each stage of this chain provides opportunities for laundering—whether through the illegal import of additives, manipulation of invoices, or the sale of adulterated products under legal labels. The economic reach of these activities is vast, affecting not only competition and consumer trust but also the fiscal stability of municipalities and states.

By embedding itself within legitimate enterprises, the PCC has blurred the boundaries between the formal and informal economies. This economic legitimacy provides the foundation for an even more sophisticated operation: the use of fintechs and investment funds to conceal and multiply criminal assets within the national financial system.

The Use of the Financial System and Fintechs

The operations from September and October were only possible due to “Carbono Oculto” (Hidden Carbon). This was the biggest operation against organized crime in Brazil’s history, and it had been carried out by the Brazilian Federal Revenue (RFB) and the Federal Police (PF) a month earlier, on 28 August.

Hidden Carbon revealed that the PCC had built a parallel financial system capable of moving billions of reais through legitimate market structures. Rather than relying on conventional banks, the group operated through fintechs and payment institutions designed to bypass stricter regulation and reporting obligations applicable to traditional banks. These digital platforms offered what the organization most needed: speed, anonymity, and plausible legality, turning technology into a new laundering mechanism.

At the center of this structure was Avenida Faria Lima, Brazil’s financial heart and the symbol of Brazil’s modern capitalism. The investigation exposed that members of the PCC had infiltrated this environment, controlling around 40 investment funds based there, collectively managing R$30 billion in assets. Through these funds, the group financed the purchase of ethanol plants, gas stations, port terminals, farms, and luxury properties, effectively merging illegal funds with the legitimate economy.

Authorities also uncovered fintechs operating as “parallel banks” that handled over R$46 billion between 2020 and 2024. These entities maintained so-called “contas-bolsão”—aggregate accounts at traditional banks where clients’ funds were pooled—making it nearly impossible to identify the true source of the money. By exploiting regulatory blind spots, such as weaker anti–money laundering controls and the absence of detailed reporting to tax authorities, the network successfully concealed massive financial flows.

What made the scheme especially dangerous was not only the scale of the laundering but also its integration into Brazil’s formal financial elite. Faria Lima, often referred to as the country’s “Wall Street,” provided both legitimacy and technical sophistication to criminal operations that mirrored the behavior of legitimate corporate conglomerates.

The PCC’s financial reach extends beyond Brazil. Investigators have uncovered links between its investment structures and offshore entities in other Latin America countries, where profits from drug trafficking are laundered and reinvested in the legal economy.

Risky Connections

It is imperative that legitimate companies in Brazil become aware of the growing risk of associating with businesses controlled by criminal factions. This connection, frequently camouflaged in complex corporate structures and seemingly licit contracts, not only distorts fair competition but also exposes the organization to being used as a key component in sophisticated money laundering schemes. The infiltration of organized crime into the formal economy is subtle, but the risk is tangible and escalating across various sectors.

The most immediate consequence is the loss of reputation and market credibility for the whole sector, resulting in the flight of investors, difficulties in obtaining credit, and the termination of international partnerships that demand high compliance standards. Additionally, there are legal risks, including the potential for criminal, administrative, and civil liability, not only for the company but also for its directors and managers, for negligence.

To mitigate this danger, a robust culture of compliance and due diligence across partners, suppliers, and clients is indispensable. The prior verification of third parties’ history and financial health, along with continuous monitoring of atypical transactions and inexplicable corporate changes, serves as an essential preventive barrier. Only an active stance in risk management and corporate ethics ensures the business is shielded against the threat of illicit capital and maintains its integrity.

This fusion of illicit economy with the mainstream finance sector marked a new stage in organized crime’s evolution—one where power is accumulated not through violence, but through capital, investment, and influence.

Conclusion

The operations “Carbono Oculto”, its subsequent phase, “Operação Spare”, and the other smaller operations successfully identified, exposed, and severely disrupted the specific financial schemes used by the PCC in the financial system.

The operations marked a major turning point by publicly proving that the crime organization had moved from street-level operations to the “top floor” of the Brazilian financial system. They were crucial steps that significantly damaged the PCC’s financial arm and exposed its sophisticated methods of operating in the legal economy. However, they are part of an ongoing fight, not the final solution to an organization of the PCC’s scale and complexity.

In addition, these operations are excellent models for what should be done in Rio de Janeiro and other major Brazilian cities. These operations showcase a paradigm shift in combating organized crime, moving away from relying primarily on high-risk, violent street operations towards a more effective strategy focused on financial intelligence and systemic disruption. They provide a blueprint for attacking the economic core of criminal groups like the PCC and Rio’s Red Command (CV) and Militias.