Summary

Brazil is facing a growing public health emergency linked to the consumption of methanol-tainted alcoholic beverages. Since the first reports in August, the number of methanol poisoning cases has continued to rise, prompting nationwide concern and renewed scrutiny of illegal alcohol production and distribution networks. The contamination, traced to counterfeit spirits produced with adulterated ethanol, has already resulted in multiple deaths and severe intoxications, exposing major failures in product control and consumer safety. The crisis has affected both individuals and the broader economy, shaking public confidence in the beverage and hospitality sectors.

Recent Cases

According to the latest report from Brazil’s Ministry of Health, released on 31 October, there have been 133 reported cases of methanol poisoning across the country. Of these, 59 have been confirmed and 45 remain under investigation, while 682 reports have been dismissed. The confirmed cases are concentrated mainly in São Paulo (46), followed by Paraná (6), Pernambuco (5), Mato Grosso (1), and Rio Grande do Sul (1). São Paulo has 9 ongoing investigations; other states investigating cases include Pernambuco (20), Piauí (5), Paraná (4), Mato Grosso (2), Rio de Janeiro (2), Bahia (1), Mato Grosso do Sul (1), and Tocantins (1). So far, there have been 15 confirmed deaths, nine in São Paulo, three in Paraná, and three in Pernambuco, with six additional fatalities still under investigation in six different states.

Behind these statistics, there are stories of personal tragedy. In São Paulo, Rafael Anjos Martins, 28, died after remaining in a coma for 50 days because of a tainted gin purchased from a local wine cellar. Radharani Domingos, 43, an interior designer, lost her sight after consuming vodka-based cocktails in the Jardins district. In São Bernardo do Campo, Bruna Araújo de Souza, 30, fell seriously ill after attending a “pagode” concert where she drank vodka mixed with juice. Wesley Pereira, 31, collapsed into a coma after drinking whiskey at a party, and Marcelo Lombardi, 45, died from organ failure after consuming contaminated vodka at home.

These cases illustrate how adulterated beverages have reached consumers from different backgrounds and locations, revealing a widespread and dangerous distribution network that extends far beyond isolated incidents.

The Path of Methanol

The São Paulo Civil Police revealed on Friday (17/10) the detailed route of the contaminated ethanol responsible for producing methanol-tainted beverages that caused two deaths in the Mooca district, in São Paulo’s East Zone, and left another man blind in the South Zone. Investigators traced the origin of the substance to two gas stations located in Santo André and São Bernardo do Campo, in the ABC Paulista region.

According to the police, the ethanol sold at these stations had already been mixed with methanol before reaching the clandestine beverage producers. The contamination likely stemmed from a large-scale fuel adulteration scheme connected to the PCC, Brazil’s most powerful criminal organization, which has been expanding its control over the fuel trade. This “spiked” ethanol was then purchased by a clandestine producer who used it to manufacture vodka, gin, and other distilled beverages without knowing it was contaminated.

The counterfeit beverage operation was coordinated by Vanessa Maria da Silva, who was arrested last week. Her ex-husband, father, and brother-in-law were also involved, participating in production, bottling, and distribution. Police identified the suppliers of the bottles used in the scheme — a packaging depot located directly across from one of the gas stations under investigation — which greatly facilitated the group’s logistics.

Forensic analyses revealed methanol concentrations exceeding 40% in the seized samples—an alarmingly high level, considering that concentrations above 0.1% are already toxic to humans. According to São Paulo’s Secretary of Public Security, Guilherme Derrite, those arrested were not members of organized crime but rather victims of a broader network profiting from fuel adulteration.

The exposure of this supply chain revealed how deeply illegal fuel operations can affect other sectors—an effect soon felt across the country’s foodservice and beverage markets.

What Is Methanol and Why It’s Dangerous

Methanol (CH₃OH) is a highly flammable, colorless, and toxic chemical compound with a smell like regular alcoholic beverages. It is a simple type of alcohol widely used in industrial applications such as fuel production, solvents, and antifreeze. However, unlike ethanol—the type of alcohol found in drinks—methanol is not safe for human consumption.

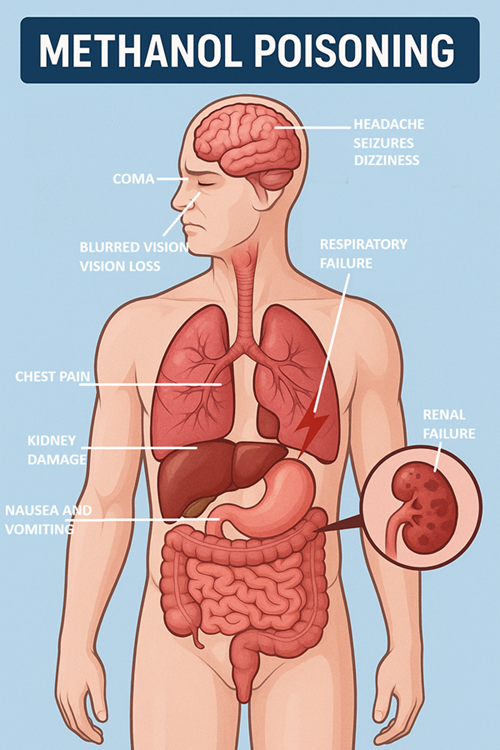

Even small amounts of methanol can cause severe poisoning when ingested, inhaled, or absorbed through prolonged skin contact. Once inside the body, the liver metabolizes methanol into formaldehyde and formic acid, substances that interfere with the central nervous system and lead to metabolic acidosis. These reactions cause damage to the optic nerve, brain, and other organs.

Early symptoms of methanol poisoning can easily be mistaken for those of regular intoxication or a hangover. They include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, confusion, and blurred vision. As the condition progresses, it can lead to blindness, respiratory failure, coma, or even death due to multiple organ failure.

Doctors warn that one of the greatest risks lies in the delay of treatment—because the initial signs often appear mild and non-specific. Rapid medical attention is essential, as the toxic byproducts accumulate quickly in the body. Laboratory tests and the administration of antidotes such as medopizole or ethanol can prevent irreversible damage if applied early.

Economic Impact

September was a challenging month for Brazil’s foodservice sector. After three months of relative stability, bars and restaurants experienced a new decline in sales: consumption dropped 4.9% compared to August and 3.9% compared to the same period in 2024. Despite being the epicenter of most methanol poisoning cases, São Paulo was one of the states least affected economically by the crisis.

The data comes from the Abrasel-Stone Index, a monthly survey conducted by the Brazilian Association of Bars and Restaurants (Abrasel) in partnership with Stone, based on financial transactions from establishments in 24 states. The results reflect the combined impact of health and economic pressures that continue to weigh on out-of-home consumption, including counterfeit drinks, persistent inflation, and high household indebtedness.

The spread of contaminated drinks has generated widespread distrust among consumers, particularly in bars and nightclubs. Many people have chosen to reduce their visits to establishments serving spirits or to switch to safer alternatives such as beer or non-alcoholic beverages. Bars that specialize in mixed or distilled drinks reported losses ranging from 20% to 25% in September alone.

In São Paulo, the state’s diversified market—marked by a strong presence of restaurants, cafés, and delivery services—helped cushion the blow, limiting the sales decline to 2.7%. According to Stone economist Guilherme Freitas, this diversification supported a faster recovery in consumer confidence in the formal sector, although the initial impact was immediate and severe for smaller venues.

While the economic effects have begun to stabilize in major urban centers, the episode revealed how fragile the sector remains in the face of public health scares and weak regulatory control. Strengthening prevention mechanisms and improving consumer awareness are now essential steps to prevent similar crises from occurring again.

The Illegal beverage market

A study by the Research and Statistics Center of FHORESP, the Federação de Hotéis, Restaurantes e Bares do Estado de São Paulo, released in April 2025, indicated that 36% of beverages sold in Brazil were fraudulent, counterfeit, or smuggled. According to the report, wines and spirits are among the products most affected by counterfeiting. One in five bottles of vodka sold in the country is adulterated, according to the survey.

The Brazilian Forum on Public Security (FBSP) has highlighted the market for adulterated beverages as a highly lucrative, large-scale criminal activity in Brazil, involving billions of reais and often associated with organized crime.

A study by FBSP, entitled “Follow the products: product tracking and combating organized crime in Brazil”[1] estimated that the illegal beverage market generated approximately R$ 56.9 billion in the country in 2023. The FBSP points out that this market is the second largest exploited by criminal factions, second only to illegal fuels. In 2022, the profit of organized crime from counterfeit beverages was reported to be greater than the revenue of the country’s largest brewery.

According to the study, there has been significant growth in the clandestine alcohol market, with a 224% increase in organized crime’s revenue from these activities between 2017 and 2023. The number of counterfeit beverage factories also showed a considerable jump in just a few years.

Prevention and Consumer Guidance

Methanol cannot be detected by taste, smell, or appearance, and contaminated beverages often seem identical to their legitimate counterparts. This makes relying on “home tests” or sensory evaluation extremely dangerous, as it can delay seeking urgent medical care. Consumers must remain vigilant and look for potential warning signs when purchasing alcoholic drinks.

Some indicators of possible adulteration include unusually low prices, informal points of sale, unpleasant or irritating odors, poorly printed or crooked labels, misspelled words, absence of a tax identification number (CNPJ), missing batch or expiration dates, broken seals, and unexpected cloudiness or color changes in beverages that should be clear, such as vodka, gin, sake, and cachaça. Even if none of these signs are present, safety is not guaranteed, as adulterated products can appear normal.

To reduce risk, it is crucial to buy alcoholic beverages only from reliable and authorized sources, such as established supermarkets. Keeping a receipt or proof of purchase is also recommended, as these documents provide supplier details and purchase information, which help with traceability and support consumers in case of complaints or recalls.

Conclusion

The methanol contamination crisis, while a severe public health concern, has also brought to light the vast, hidden market for counterfeit and adulterated beverages. This development threatens the economic security and credibility of legitimate companies, damaging their reputation, discouraging investment, and eroding public trust in regulatory and inspection schemes.

Combating this problem requires coordinated efforts between authorities, the private sector, and consumers. Stronger inspection, effective traceability systems, and public awareness campaigns are essential to disrupt the supply chains used by criminal networks to distribute contaminated products. At INTERLIRA, we provide comprehensive brand protection against counterfeiting. Our process involves revealing and monitoring irregular distribution channels and conducting deep analysis to uncover the production and distribution schemes of illicit goods. By collaborating closely with public authorities to carry out enforcement raids, we help safeguard authenticity and consumer safety, actively contributing to a more secure business environment.

[1] https://publicacoes.forumseguranca.org.br/items/5c49e7c2-f01f-42c8-ae13-83d8fa9987c6